Gino de Dominicis was one of the most interesting and exceptional artists of the 20th century. His work focuses on such themes as the immortality of matter, space and time, and invisibility. “Asta in equilibrio,” which found a new home in November for €222,600, is perfectly exemplifies his metaphysical approach.

Gino de Dominicis was one of the most versatile and complex characters of our time, and one of the most interesting artists of the 20th century. His work is distinct amongst the many artistic currents that developed from the 1960s onwards.

In his bio for the 57th Venice Biennale in 1997, de Dominicis describes himself as follows: “Gino de Dominicis, painter, sculptor, architect. Ancona 1947. His work is characterised by an independence from the various artistic trends that have developed since World War II. He exhibited his works in 1966 for the first time and subsequently in numerous exhibitions both in Italy and abroad. At his own will, there are no catalogues or books about his œuvre. He does not ascribe to photography any documentary value or advertising role for his own works.”

Always a controversial figure, de Dominicis focused his research on the immortality of matter, space and time, invisibility, and the centre of his existence as a man and artist, shrouding himself in an aura of mystery. This was consolidated by his refusal to allow his catalogues to be published, his exhibitions to be documented, or for himself or his work to be photographed. Photos of him are extremely rare; he only posed for a portrait once, for the photographer Elisabetta Catalano.

Photo: Courtesy by O. Jacorossi, Rome

He settled in Rome in 1964, for a long time giving as his only contact details the addresses of hotels in the city centre, where he could often be seen, clad in dark colours, keeping an almost unchanged image through the years, as is visible in the few existing photographs of him from the 1960s onwards.

At the Venice Biennale in 1972, to which he was invited by Renato Barilli, he exhibited the work that is probably his best known because of the strong reaction in the media and the legal controversies it stirred. “La seconda soluzione di immortalità (l’universo è immobile)” [“The Second Solution of Immortality (The Universe is Immobile)”] shows a young man with Down’s syndrome, Paolo Rosa, sitting motionless in a corner of a rectangular room that opens to the external gardens, near him are –

as was written on panels – an “invisible cube,” a “coloured rubber ball dropped from two metres in the moment before it bounces,” and a volcanic stone “waiting for a random general molecular movement in one direction so as to create a spontaneous movement of matter.”

Simone Carella, who was an assistant to de Dominicis in Venice, says: “Gino regarded the room as a summa of what he had done until then. One of the reasons he chose that room is that it opens onto a garden, so it was reachable without having to walk through the other rooms. The skylights in the roof had been covered. The first thing Gino did was ask for the covers to be removed from the skylights in order to let daylight in. Natural light, the door that opens towards the outside: his work had to be in contact with the universe. Then he asked me to look for a person who was supposed to represent this second solution of immortality, a young man who had kept the attitude of a child.”

Within the framework of his research concerning the immortality of the body, in keeping with his attempt to stop time, de Dominicis “disappeared” and “reappeared” in the Pio Monti Gallery in Rome, repeating the same exhibition in the same place one year apart (14 January, 1977–14 January, 1978), thus suggesting the possibility of an immutable, eternal existence.

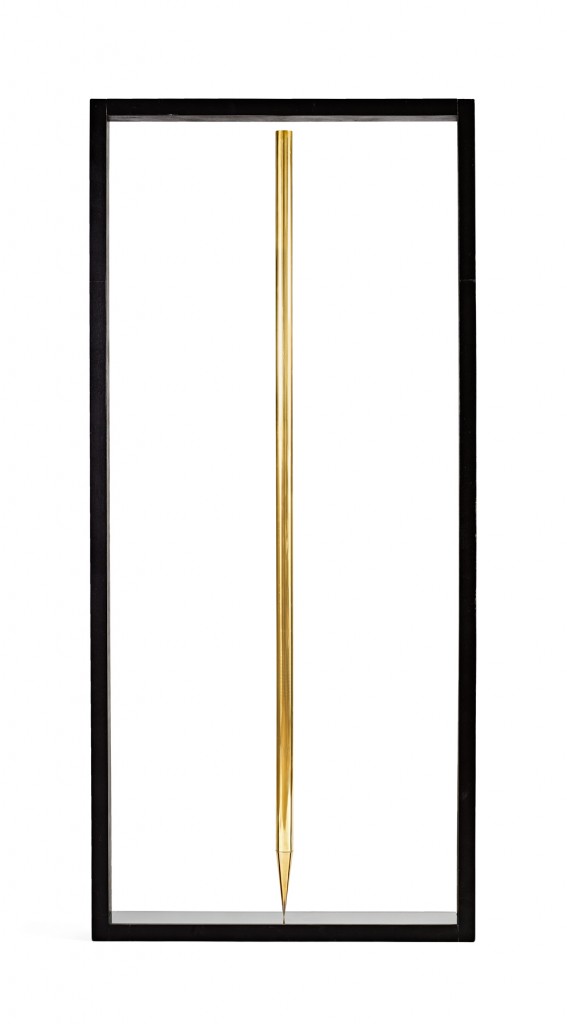

The motif of balancing poles, or rods, shiny and gilt, magically standing on the floor without any apparent support, recurs in many of Gino de Dominicis’ works from 1967 onwards. “Equilibrio 1” (“Balance 1”) appeared in 1969, when it was exhibited at L’Attico Gallery in Rome in what was then the artist’s first solo exhibition. The verticality of the pole is a symbol of the link between earth and heavens, it is an ascending path between the earthly and the divine, a firm, almost immortal point around which the universe develops.

The poles vary in size according to the space in which they are to be displayed. They are kept in balance by means of the force generated by the magnets placed above them and an iron cylinder installed in the poles themselves. At a later stage, the balancing pods were either placed within a “niche” or a sort of frame, which was either black or white, or they were associated with more complex installations.

In “Il tempo, lo sbaglio, lo spazio” (“Time, Error, Space,” 1969), the pole balances on the right index finger of a human skeleton on rollerblades lying on the floor, next to the skeleton of his dog on a leash. In the contemporary art collection at Rivoli Castle, Turin, the pole stands on a large black stone, whilst at Museo di Capodimonte in 1986 the pole on display is white and stands on a red stone.

A further example is the monumental 16-metre pole displayed in 1990 within the group exhibition “Roma Anni ‘60” curated by Maurizio Calvesi and Rossella Siligato at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni.

(myART MAGAZINE No. 06/2015)