Lawyer, farmer and painter, Werner Berg created art of international significance in the secluded province of Carinthia. He saw greatness of form in the juxtaposition of humanity and landscape, lending his work a figurative and a spiritual dimension.

Art and Life

Carinthia, 1930. Newlyweds, Werner and Amalie Berg, purchase Rutarhof, a remote mountain farm in Lower Carinthia near the 1918 border with the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the border to modern-day Slovenia. Both Werner and Amalie are lawyers with doctorates and little agricultural experience to speak of; the former has recently become a painter. What they seek is nothing less than a primeval way of life, which is to say one devoid of romance and free of normative social conventions. In 1931, Werner Berg – possessed of the necessary naiveté, iron will, remarkable consistency, and support from his wife – embarks on an active life-art experiment in and with nature. It is a vision he will continue to implement for the next 50 years.

Their careers might have taken an entirely different course. Born in 1904 in Elberfeld, a town that is now part of the German city of Wuppertal, Werner Berg studied law in Bonn and Cologne after the war as a matter of practicality and necessity. By age 26, he had already obtained his doctorate and been offered an assistantship in Vienna, where he met his future wife Amalie “Meiki” Kuster – daughter of a Viennese dairy farming family – and rediscovered his love of art. Werner Berg became a painter.

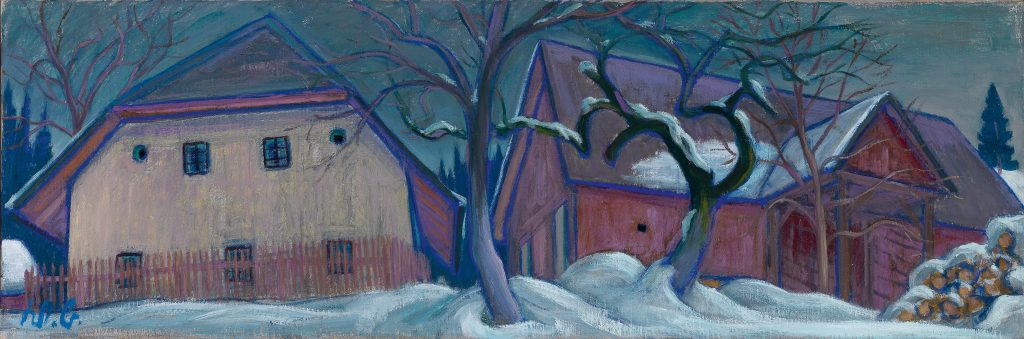

Rutarhof in Carinthia

oil on canvas, 40 x 120 cm, price realised € 67,400

Academic theory and drills were not Berg’s cup of tea. The young artist felt compelled to live life authentically, to draw his artistic inspiration and strength from the simplicity and primacy of life and toil. His southern Carinthian farm offered a place to do just that. Berg was quick to build a studio on top of a sheepfold. It was a place to which he would retreat after his work in the fields was done, but also a haven that allowed him to give formal expression to his many impressions and thoughts. Though unquestionably drawn to the surrounding nature and the farm’s own magnificent view of the valley, it was the particular, almost archaic culture of this Austrian-Slovenian border region that became a source of an almost infinite fascination for the painter. The artist describes solitary visits to the markets, religious festivals, or miscellaneous day-to-day encounters as offering “a wealth of sights in which, beside anecdote and folklore, one can effortlessly discover great form, timeless goings-on and a richly visual mystery” (Werner Berg, 1984, p. 32).

Lost Generation

As an artist, Werner Berg belonged to the so-called “lost” generation that had been forced to forge a professional path amid the ruins of the First World War. And yet, rather than indulge in the debauchery and urban decadence sought by so many of his era, Berg chose conscious solitude instead. He aimed to give his artwork an anchoring, a depth, that set it apart from the era and lent it a fundamental sense of authenticity. Like Wilhelm Leibl in Bad Aibling, Upper Bavaria, or Paul Gauguin, who decades earlier had sought the unspoilt life in Brittany and in Tahiti, Werner Berg opted – even more radically – to fuse art with everyday life as a farmer.

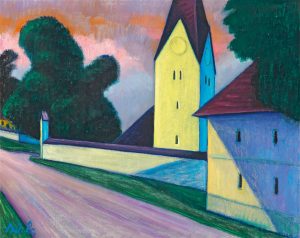

oil on canvas, 63 x 89 cm, price realised € 219,900

Berg’s concept, combining work, family and art, bore fruit in the early to mid-1930s. He had exhibitions in Berlin, Hamburg, Bochum and Cologne, garnered awards, attracted collectors. Nonetheless, his art – with its roots in German Expressionism and the paintings of Munch, Nolde and Kirchner, with whom he also exchanged ideas – was declared “degenerate” in 1937. His paintings were largely destroyed. Werner Berg withdrew completely to Rutarhof until a tour of military duty in 1941. That same year saw him deployed to the Arctic front, where he would remain until the end of the war and was taken prisoner, and where he also created a series of works. Upon returning, he poured boundless energy into his calling as both a farmer and artist. He fostered gallery contacts, participated in the Venice Biennale and, in 1950, met the poet, Christine Lavant. The ensuing, rather stormy relationship culminated in Berg’s mental breakdown and subsequent intense, final period of work. His palette became even more intense, as hues became vehicles of expression that could be interpreted in any number of ways.

Colour and Form

im Dorf (Summer Evening

in the Village), oil on canvas

76 x 96 cm, estimate € 140,000 – 180,000

Just as colour was foundational to Werner Berg’s paintings, so too was the fathoming of surface and form. In the absence of any active plot, we find an emphasis on the “state of being”. The pause gives his figures an air of dignity; the “human being” appears in all its timeless meaning and significance. Time is a crucial component of Berg’s paintings in general. To him it meant immortalising the precious moments of a culture that he had come to call home. A great, atmospheric calm emanates from his paintings: all that is exalted, loud, turbulent is captured in a gentle if compelling rhythm of lines, shapes and colours. It is an aspect that is especially evident in the paintings without figures, among them “Summer Evening in the Village”, where a rigorous interlocking of cubic forms, diagonal lines, and luminous colour fields brings to bear fascinating questions of time, place, abstraction, and subject.

His output from 1921 until 1981, the year of his death, also includes a stream of woodcuts in addition to his painting, a practice consistent with German Expressionism.

Artistic Heritage

1968 saw the founding of Werner-Berg-Galerie on the main square in Bleiburg. The gallery opened in 1972 following renovations with a selection of works chosen by the artist. By this time, Berg was no longer unknown. His work had featured in exhibitions throughout Europe, as well as in Egypt and Lebanon; publications on his work included a catalogue raisonné by Kristian Sotriffer. Though gratifying, these efforts also demanded a great deal of energy. The painter found his closest confidant, administrator, and caretaker of his work in his grandson, Harald Scheicher. Scheicher, who continues to look after Berg’s estate, now serves as director of the Werner Berg Museum.

Works by Werner Berg have long fetched record prices at Dorotheum auctions. The international context of these auctions shows time and again the quality and art-historical significance of the artist’s œuvre.

Literature: Harald Scheicher (ed.): Werner Berg. Seine Kunst, sein Leben [Werner Berg: His art, his life]. Klagenfurt 1984

AUCTION

Modern Art, 31 May, 5 p.m.

Palais Dorotheum, Dorotheergasse 17, 1010 Vienna

20c.paintings@dorotheum.at

Tel. +43-1-515 60-358, 386