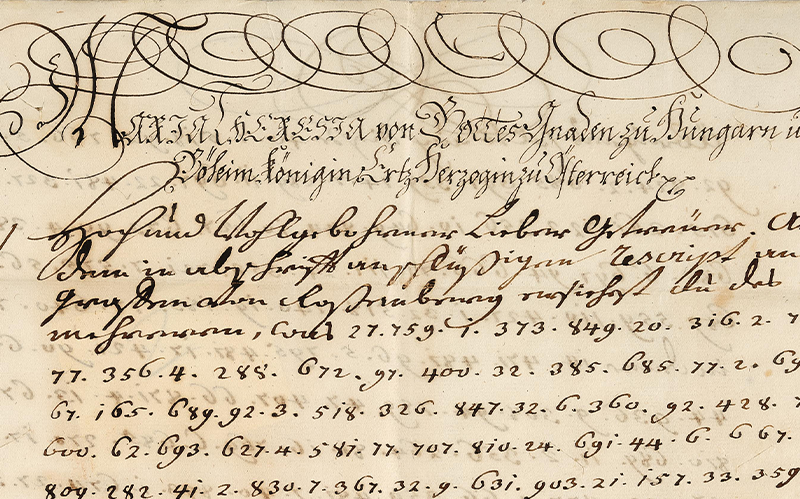

A coded letter from Maria Theresa which will be up for sale on 17th December 2024 provides an insight into the secret diplomatic transfer of information in the 18th century.

On the eve of the Second Silesian War against Prussia (1744/45), Empress Maria Theresa addressed a secret letter, signed in her own hand, dated 31 June 1744, to Count Nikolaus Esterházy (1714–1790), who was at that time her time envoy to the allied court of the Electorate of Saxony in Dresden. For outsiders or enemy agents, imperial mail from Vienna contained only mysterious series of numbers, but Esterházy belonged to an exclusive circle of high-ranked dignitaries who possessed the closely guarded cipher used in these communications and was therefore able to decipher the complicated secret code.

Even today, historic ciphers present historians and cryptanalysts with sometimes unsolvable problems if the associated decryption key is not known. It is therefore a stroke of luck that the original letter from the Empress was accompanied by a copy of the cipher key which is held in the Austrian State Archives, meaning that the Imperial note can be transcribed into plain text and its contents can be almost completely deciphered.

As can be seen from the cipher table, the code used is not a cryptographic system which replaces individual letters with other letters, numbers or characters, but a numerical cipher which lists nouns, proper names, verbs and adjectives in alphabetical order as a word replacement system, without distinguishing the type of word, representing them as three-digit numbers. For example, the number 400 means the word battle, 401 stands for Silesia and 402 for the verb close. To make decoding even more difficult, the coding system starts the alphabet with the letter K and occasionally intersperses blenders, i.e. digits with no meaning, in the sequence of numbers.

As Count Esterházy was familiar with this system, he was able to glean the disturbing news from the Empress’s letter that Prussian diplomats had begun secret negotiations with the Ottoman Empire, and furthermore, he could decode the Empress’s instruction to him: he was to come to an understanding with the Saxon authorities, along various precisely defined lines. It is not clear who is meant by ‘the Greek’ mentioned in the letter who was to be arrested in Hungary, but it is probably a code name known to Esterházy. Finally, the Empress describes her main opponent, King Frederick II of Prussia, as a ‘dangerous neighbour who does not bind himself to any treaty’.

As coded secret letters were often deliberately destroyed after being deciphered, the letter to Esterházy is a rare example of secret diplomatic communication in the 18th century.

AUCTION

Autographs, manuscripts, documents

17 December 2024, 2 p.m.

Palais Dorotheum, Dorotheergasse 17, 1010 Wien

Viewing: 12. – 17. December 2024

books@dorotheum.at

Tel. +43-1-515 60-389