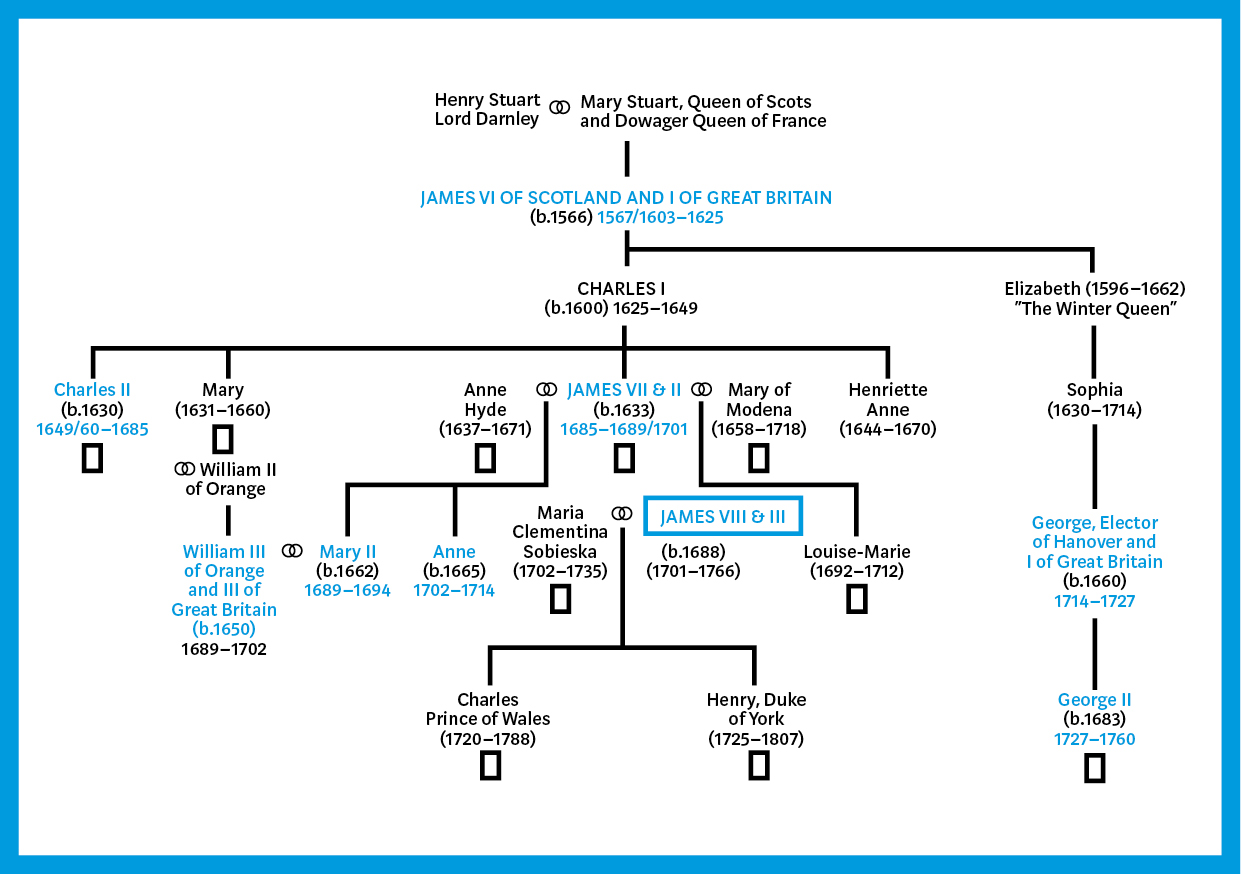

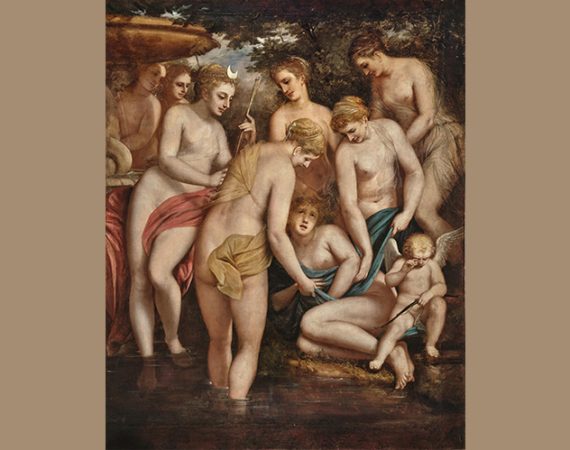

The portrait of Prince James Francis Edward Stuart as Prince of Wales by Nicolas de Largillière is an important rediscovery. Previously only known from an engraving by Gérard Edelinck, it testifies to the political and religious turmoil of the era, as art’s employment in service of propaganda is testament to the political and religious turmoil of the time.The Stuart royal family had already ruled Scotland for over two hundred years when James VI succeeded Queen Elizabeth I as James I of England in 1603. Subsequently the kingdoms of Scotland, England and Ireland were ruled by the same monarchs.

James I was succeeded by his ill-fated son Charles I, who was executed. Britain and Ireland briefly became republics, but the Stuart family were restored to the three monarchies under Charles II in 16560, who was succeeded by his brother King James II of England and Ireland, James VII of Scotland. During James’ three-and-a-half-year reign he became involved in the political battles between Catholics and Protestants and a severe crisis developed after the birth of his eldest son Prince James Francis Edward Stuart on 10 June 1688 at St James’s Palace in London, who is here depicted aged three. As the son of James II of England and his second wife, the Roman Catholic Mary of Modena, James Francis Edward became the heir to the English, Scottish and Irish thrones. The prince’s birth caused a sensation. Occurring five years after his father James II ́s marriage, it was largely unanticipated by a number of British Protestants, who had expected his daughter Princess Mary, from his first marriage to Anne Hyde, to succeed to the throne. Mary and her younger sister Princess Anne had been raised as Protestants.

As long as there was a possibility of one of the Protestant princesses succeeding him, the king’s opponents saw his rule as a temporary inconvenience. The birth of a son to James II displaced the Protestant heir presumptive and the creation of a Catholic dynasty now threatened. James’ policies of religious tolerance and his attempts to relax the penal laws imposed on Catholics after 1685, as well as his close ties to Catholic France, had met with increasing opposition by members of leading political circles. Influential English Protestants now aligned themselves with the Dutch stadtholder William of Orange, who was married to James II’s eldest daughter, Princess Mary. William arrived with a large invasion fleet in November 1688 and, after limited resistance and his victory at the battle of Reading, James II was forced to flee his kingdom.

On 9 December, Mary of Modena, disguised as a laundress, smuggled her six-month old son to France. Young James was brought up at the Château de Saint- Germain-en-Laye, near Versailles, which his cousin Louis XIV had given to the exiled James II as a residence. He and his family were held in great esteem by the French king, and they were frequent visitors at Versailles, where Louis XIV and his court treated them as ruling monarchs.

In effect, the revolution that placed William and Mary as joint king and queen on the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland in February 1689 ended the chance of Catholicism being re-established as the state religion in Britain and Ireland. For the Catholic population the effects were disastrous both socially and politically. Catholics were denied the right to vote or have a seat in parliament for over a century. They were also denied commissions in the army and the monarch was forbidden to be a Catholic or marry a Catholic.

After his father’s death, Prince James Francis Edward Stuart claimed the English throne as James III and the Scottish throne as James VIII. He was recognised as king by his cousin Louis XIV of France, by Spain and by the Papal States. However, as a result of his refusal to convert to Protestantism after the death of his half-sister Queen Anne, he was not recognised by the English themselves and his titles were forfeit under English law. James’ second cousin, the Prince-Elector George of Hanover, a German-speaking Protestant, became king of the recently created Kingdom of Great Britain as George I in 1714.

The present painting is an excellent example of the rich artistic output of the exiled Stuart court in France. Regal in every sense, it clearly aimed to outshine Prince James’ counterpart in England. It is fascinating to conjecture how life and culture in Britain and Ireland might have differed had Prince James ever reigned in the country of his birth. After all, he might have had one of the longest reigns in British and Irish history, from his father’s death in 1701 to his own death in 1766.