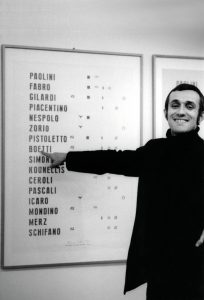

Alighiero Boetti (1940–1994) was no doubt one of Italy’s most creative and prolific artists of the second half of the 20th century. A highlight of the contemporary art auction in May is a piece from his famous Biro series.

Alighiero Boetti often took up contradictory positions during his lifetime, which prompted the art historian Achille Bonito Oliva on the recent occasion of a retrospective at the MAXXI Museum in Rome to describe him as a complex, chameleon-like character and fine intellectual. Boetti’s divisiveness is expressed not least in his signature, “Alighiero e Boetti” (“Alighiero and Boetti”), as if by dividing his name he wanted to point to diverging identities united in one person.

The Turin-born artist defies classification within the boundaries of a single art movement. His œuvre spans more than 30 years in which Boetti oscillated between different movements in an extremely eclectic way: from Arte Povera in his early creative period to Mail Art, to more conceptual approaches and back to traditional painting as well as arts and crafts. Although drawn to many styles, Boetti rejected overly romantic or transfigured notions of the artist and refused to see himself through such a lens.

The Turin-born artist defies classification within the boundaries of a single art movement. His œuvre spans more than 30 years in which Boetti oscillated between different movements in an extremely eclectic way: from Arte Povera in his early creative period to Mail Art, to more conceptual approaches and back to traditional painting as well as arts and crafts. Although drawn to many styles, Boetti rejected overly romantic or transfigured notions of the artist and refused to see himself through such a lens.

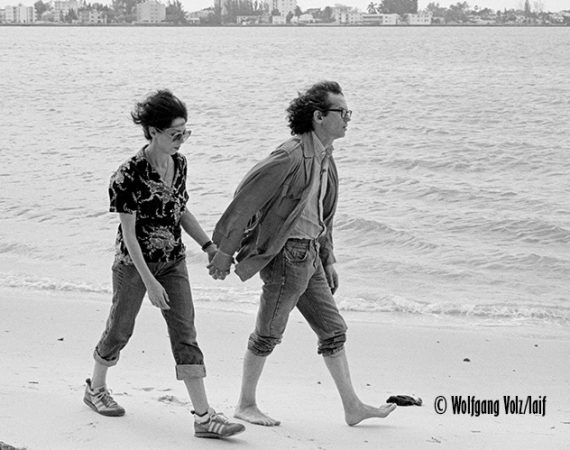

In the 1970s, Boetti was one of the first Italian artists to turn his attention to the mysterious realm of the Middle East and Central Asia, establishing particularly close ties with Afghanistan.

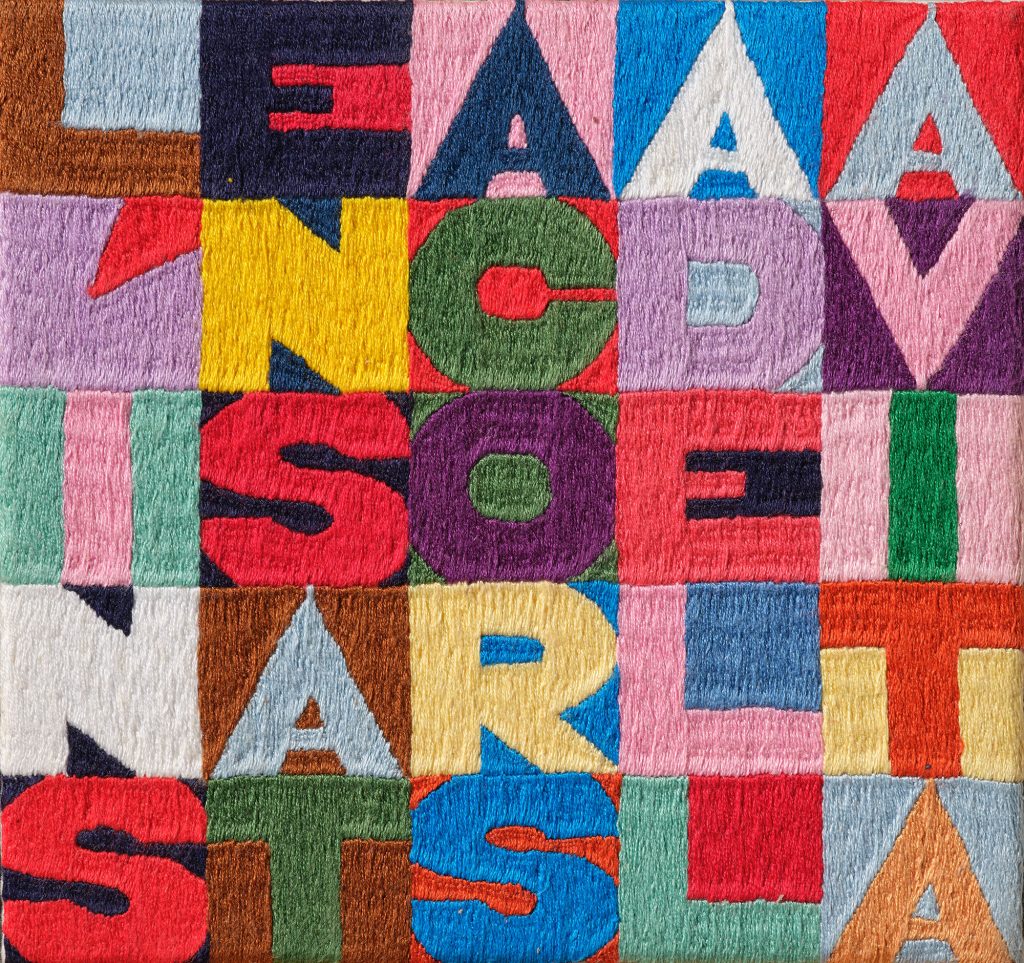

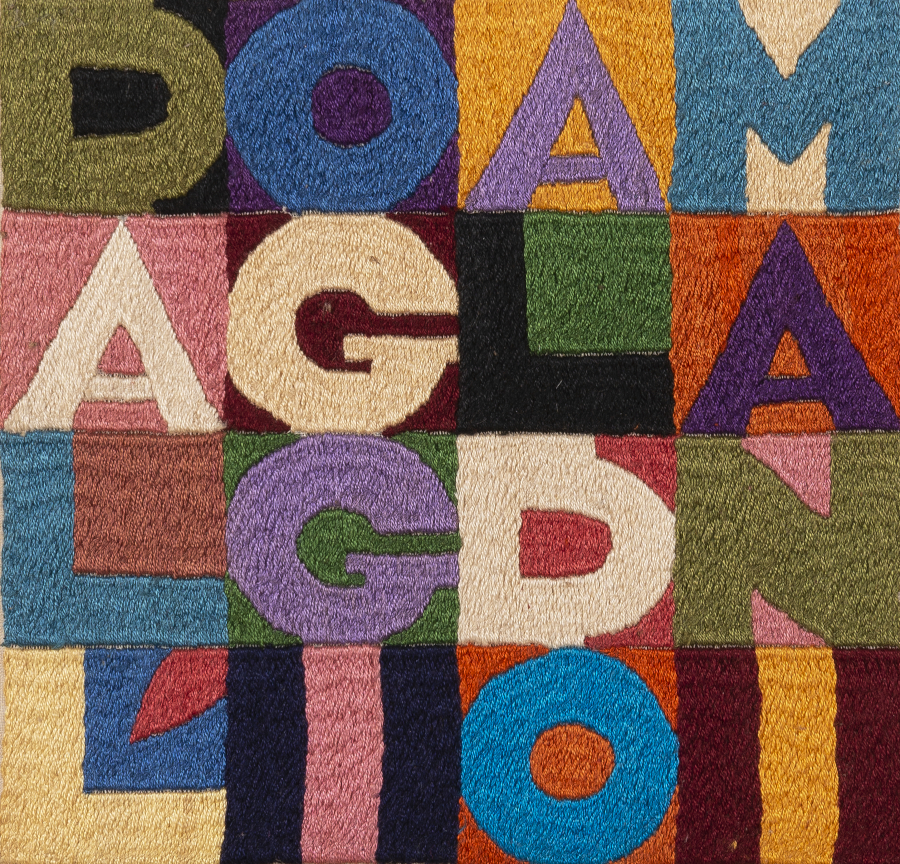

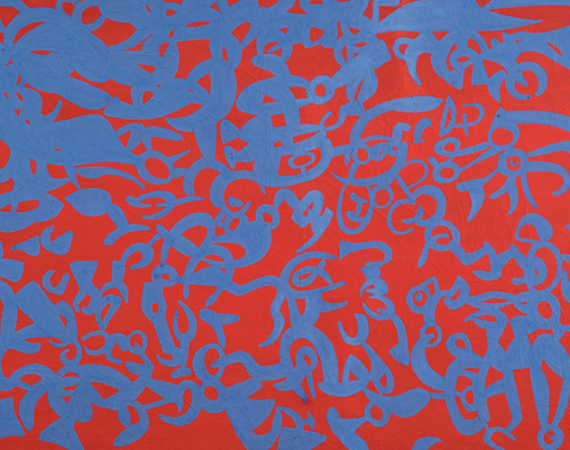

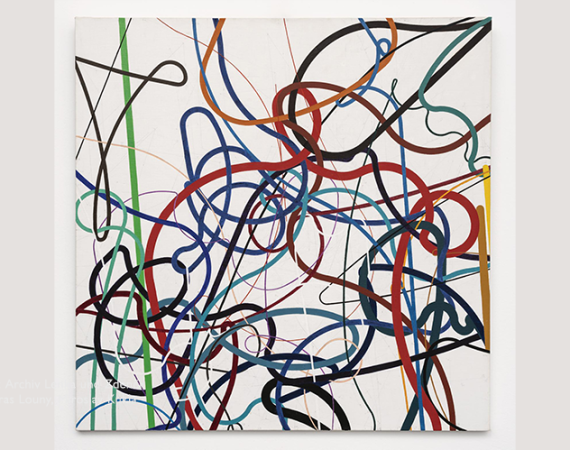

By that time, he had entered his mature creative phase, typified by a series of world maps, Mappe, which Boetti designed and whose production he entrusted to embroiderers in Kabul. Those years were characterised, above all, by the collaborative methods through which the artist embraced the world in all its pluralism and diversity, as he was strongly influenced by socialist humanism and the Marxist visions spreading across Europe at the time. Parallel to Mappe, Boetti was also working on another series based on the principle of collaboration: unlike his political maps and other embroidered pieces, Lavori Biro (ball pen paintings) were created by students, friends, or occasional collaborators, using a tool that had long led a shadowy existence in the history of contemporary art – the ballpen.

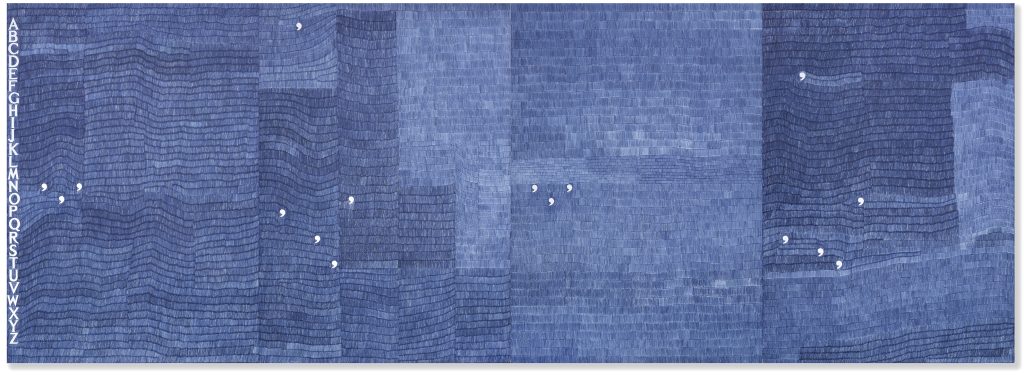

Non parto non resto from c. 1981 is a four-part polyptych of considerable size. Densely placed strokes of ballpoint ink cover the ground, creating an almost monochromatic surface reminiscent of Yves Klein’s early experiments or Giotto’s much older frescoes in Padua. The panels appear mysterious, as if they were keeping a secret that wants to be discovered. The riddle begins with the title, a vague allusion to the tragic love story of Dido and Aeneas in Virgil’s Aeneid: “Non parto non resto” (“I shall not leave, nor shall I stay”) – Aeneas, too, is torn between opposites. The constellation of strokes on the panels is interrupted by occasional commas, which look like little stars in space. These 16 commas refer to the alphabet on the first panel. They are the key – or coordinates, as it were – for the interpretation of the work. Keen observers will have no difficulty working out the arrangement of commas, which should be read from left to right and are anything but random: each comma points to an alphabetic character at its same height, thus revealing the title of the picture through a curious game of connections.

Alessandro Rizzi is Specialist for Modern and Contemporary Art at Dorotheum, where Adriano Blarasin works as an art historian.

AUCTION

Contemporary Art, 24 May 2023, 6 pm

Palais Dorotheum, Dorotheergasse 17, 1010 Vienna

20c.paintings@dorotheum.at

Tel. +43-1-515 60-358, 386