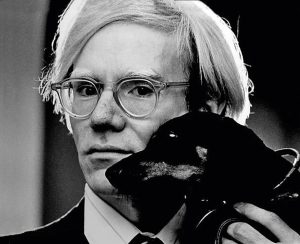

The enfant terrible of Pop Art, Andy Warhol, admired Man Ray throughout his life. He met the legendary Surrealist and Dadaist in person, in 1973 Paris. They took Polaroid photos which Warhol used as the basis for a series of portraits commissioned by the Turin art dealer, Luciano Anselmino. A fabulous, privately owned canvas from the Man Ray Seriesis included in the Post-War and Contemporary Art auction at Dorotheum in June.

With Andy Warhol, there are always at least two sides to the story. Take Man Ray, for example: Warhol photographed Man Ray in his Paris apartment on 30th November 1973. It is generally accepted by art historians that many of the principles of Warhol’s art, and Pop Art in general, had their genesis in the work of the influential U.S. photographer and experimental filmmaker. Amongst the influences said to come from Man Ray, who, like Warhol, came from a poor, immigrant background, are the repetition and reproduction of motifs, such as we see in Warhol’s series of soup cans, Marilyns, Maos, and electric chairs and so on. As an art student in his native Pittsburgh, Warhol had also experimented with the shadow-like photograms, or “rayographs” which had been pioneered by Man Ray.

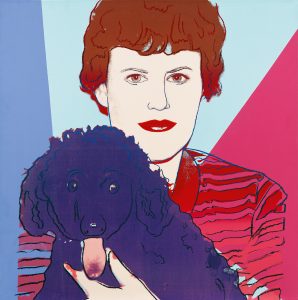

acrylic and silkscreen ink on canvas, 101 x 101 cm, estimate € 300,000 – 500,000

It may not come as a surprise to hear that Andy Warhol’s own version of the outcome of the Paris encounter is a somewhat different from the art historical narrative. In a selection of interviews entitled “I’ll Be Your Mirror”, he discussed the matter in his inimitable, dry and sphinx-like style. The only thing he could remember, he said, from his meeting with Man Ray, was his toilet seat, because it had a fabric cover. He went on to say that he “only really loved him for his name” – Man Ray. Despite this however, one thing is certain: Warhol was very much taken with May Ray and his work, as he was with Salvador Dalí: he even owned some early pieces by Man Ray.

How did these legends of Dada, Surrealism and Pop Art actually come together in 1973? The meeting between Warhol and Man Ray was arranged by the young Turin art dealer, Giovanni Anselmino, who was instrumental in popularizing Man Ray’s work in Italy in the early 1970s, thereby contributing to the artist’s gradual rediscovery after the 1950s. Anselmino (who, according to Bob Colacello, was nicknamed “Anselmino of Torino” because he “looked more like a hairdresser than an art dealer”) wanted to commission Warhol to make a series of Man Ray canvasses and prints. According to Colacello who was Editor of the renowned Interview Magazine and habitué of Warhol’s studio “The Factory”, Anselmino had probably met Man Ray in 1969 on the initiative of gallerist Alexandre Iolas who had organised Warhol’s first show in New York in 1952 (and, incidentally, was also to put on his last show in Milan in 1987).

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Bildrecht, Vienna 2022

What remains of Warhol’s legendary visit to the 83-year-old Man Ray, is a series of canvases. One of them, a typical acrylic and silkscreen portrait based on a photograph, is prominent in Dorotheum’s upcoming auction of Contemporary Art. “Man Ray” (1974), number 2635 in Warhol’s catalogue raisonné, has featured in exhibitions in the past, but has until now, never appeared on the art market. It has always been in private hands and occupies a special place in Warhol’s œuvre.

The commission from Anselmino comprised six canvasses based on photos taken at the Paris shoot. The picture coming up for sale at Dorotheum’s June sale is No.2 of the series. Warhol also used the Man Ray motif for other, small-sized series and a limited edition of 100 prints, which was supposed to feature a Henry Miller text and a Jasper Johns illustration, although this never materialised.

The Man Ray series was created at a time when “business artist” Warhol, in the manner of old masters, took on portrait commissions from dozens of rich and famous clients across the globe. The Man Ray series is not one of them; it is one of a series of portraits of people – mostly artists – whom Warhol truly admired. This is also evidenced by the fact that he kept three of his “Man Rays” for himself.

acrylic and silkscreen on canvas, 101.5 x 101.5 cm, estimate € 180,000 – 240,000

At the 1973 photo shoot, Warhol styled his Dada hero, asking him to remove his glasses, put on his mariner’s cap, and pose with a cigar in his mouth. By Warhol’s standards, the painting shows a highly individual colouring, which has been attributed to great emotion and depth of feeling. The same treatment is evident in portraits of his mother, who Warhol was very close to throughout his life. This is especially remarkable in a man whose desire was to “be a machine”, and demonstrates the ambiguity of the Pop Art chameleon Andy Warhol, who never ceases to be the subject of fascination.

In “Letter to Man Ray”, an absurdist 20-minute video monologue recorded on the occasion of Man Ray’s death in 1976, Warhol gives a performative account of his Paris photo shoot with the master. The repetitive speech reflects the principle of Warhol’s pictures: “I took another picture of Man Ray, another Polaroid portrait of Man Ray and another Polaroid portrait of Man Ray, another Polaroid portrait of Man Ray and then another Polaroid portrait of Man Ray and then I took another Polaroid portrait of Man Ray and then I took another Polaroid portrait of Man Ray. And then I took another portrait. And then I think he took another portrait of me and then he signed that one for me and I put it in my Brownie shopping bag.”

Apparently, Man Ray had no idea at the modelling session how famous his visitor was. He was recorded on an audiotape asking Warhol how he liked the Big Shot camera, and which focal length he used, but Warhol, who wouldn’t have this shop talk, replied that it was the cheapest camera and therefore his favourite remove stop.

Information: Alessandro Rizzi and Petra Schäpers, specialists in Modern and Contemporary Art

AUCTION

Contemporary Art , 1 June 2022, 5 p.m.

Palais Dorotheum, Dorotheergasse 17, 1010 Vienna

20c.paintings@dorotheum.at

Tel. +43-1-515 60-358, 386