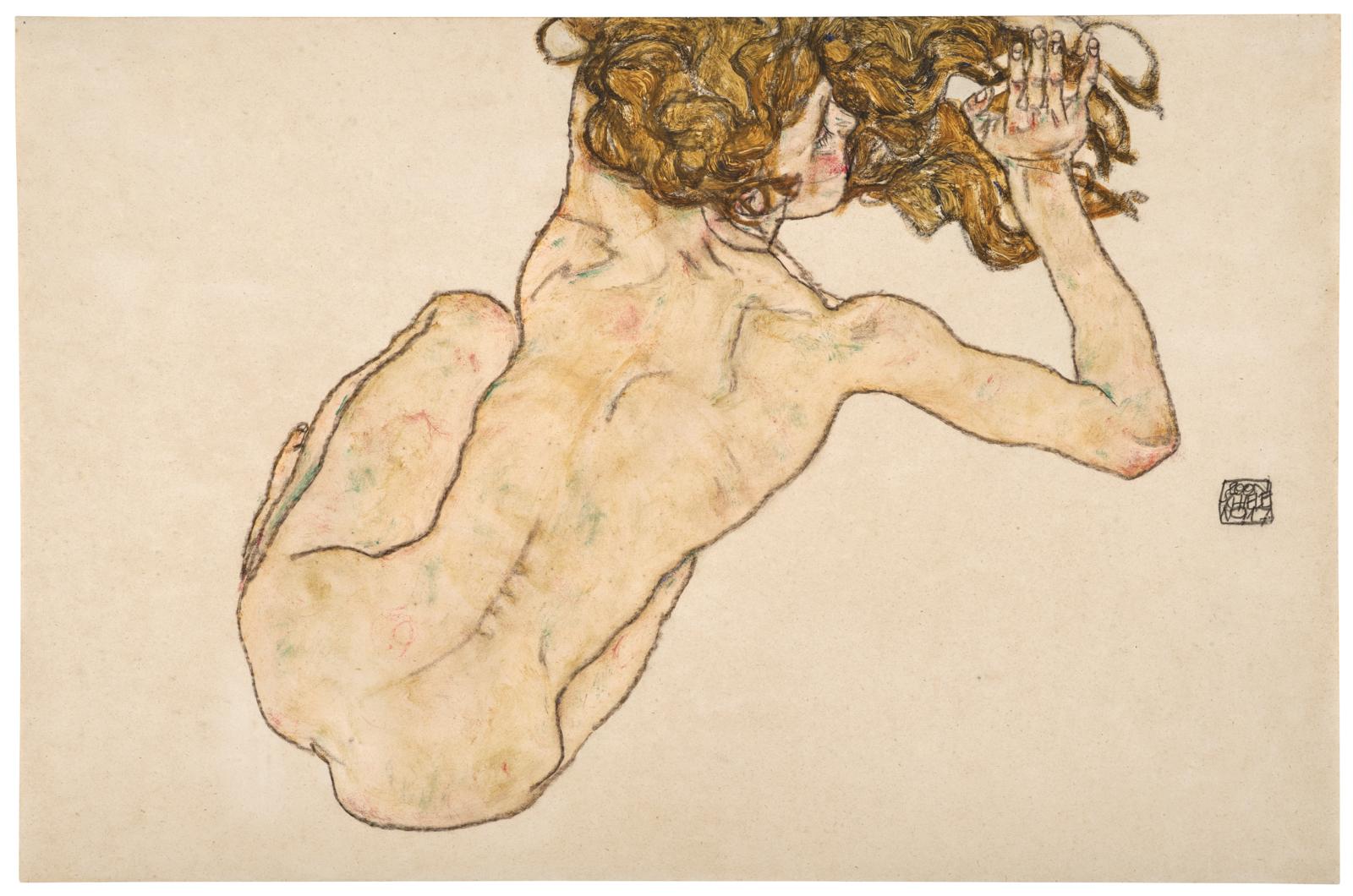

Charged with tension yet strangely remote, Egon Schiele’s female nude, made a year before his death, stands as a prime example of a new, intense phase in the great artist’s work.

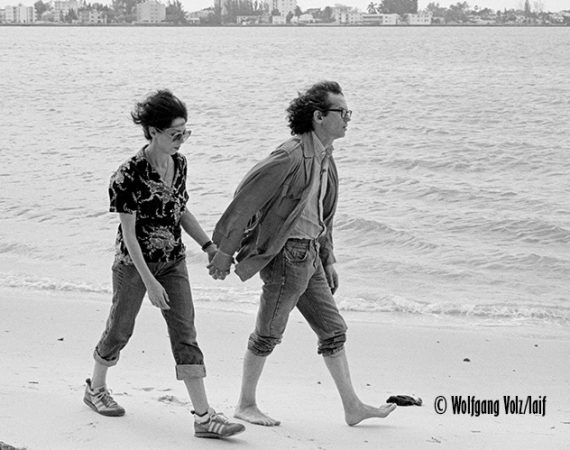

By early 1917, Egon Schiele had at last achieved success. Released from military service at the barracks in Mühling, Lower Austria, he returned to Vienna – to his studio and his young wife, Edith, whom he had married just two years before. This marked the start of a final, intense burst of creativity in which the now-celebrated artist re-examined the human figure, the body and its sexuality. He once again hired models: sometimes his sister-in-law Adele posed for him, and more rarely Edith herself.

The result was a rich body of drawings. Yet something had changed. Schiele’s gaze had shifted. The focus fell less on the expressionist turmoil of earlier years than on the body as a formal phenomenon: its twists and contortions, its spatial presence within the picture plane, and the lines that articulate it. Schiele was no longer simply depicting nudes; he was choreographing zones of tension in which models acted under his direction. In some drawings from 1917, the poses appear almost artificial, theatrical, yet it is precisely in this deliberate staging that Schiele’s new intention emerges: a formal interrogation of the body.

One model recurs throughout that year. She cannot be identified by her (mostly stylised) facial features; only her warm, reddish-brown hair – sometimes pinned up tightly, sometimes falling loose – marks her out unmistakably. She possesses a distinctive, delicate grace, a quiet presence that the artist captures with almost poetic sensitivity in the present work, Crouching nude, back view.

What immediately stands out in this 1917 back-view nude is the ease with which a line – powerful yet assured, swelling and ebbing in rhythm – shapes the female body from the undefined white of the paper. While the figure is clearly set above the lower edge, the young woman’s head almost extends beyond the upper margin – a compositional sleight of hand that enhances the sense of floating and gliding. This also accounts for the contrast between a gently reclining pose and one that is at once tightly curled and tilting slightly to the side. The angled legs, the narrow waist, the sharply defined back with its strongly emphasised spine – everything appears charged with tension yet somehow distant. Fittingly, the figure seems asleep, her head resting beside her bent arm on the fullness of her freely falling hair.

The composition lives on contrast: formally, between the strict, continuous contour drawn in bold graphite and the sparse, almost dry brushstrokes of colour that give the surface depth and physicality. Thematically, it is precisely the figure’s turned-away pose, her sleep, her inaccessibility that evoke a distinctive eroticism – not an explicit one, but one of grace, fragility and inner strength.

Ukiyo-e – ‘images of the floating world’ is what the Japanese called their art of woodblock printing, which also fascinated Schiele greatly. Everything in this drawing is in flux – the line, the body, the hair, the dream. Schiele expert Jane Kallir sums up Schiele’s work from 1917: ‘When he is good, he is extraordinarily good.’

The drawing entered a private collection in the 1980s. It was once part of Serena Lederer’s collection, as documented by her signature on the back of the sheet. Following a restitution process, the work can now be offered for sale.

AUCTION

Modern Art, 18 November 2025, 6 pm

Palais Dorotheum, Dorotheergasse 17, 1010 Wien

20c.paintings@dorotheum.at

Tel. +43-1-515 60-358, 386