Elfie Semotan is widely acknowledged as one of the world’s leading (fashion) photographers

Elfie Semotan talks to myART MAGAZINE about selfies, smileys, still-lifes and the creative value of boredom.

Dorotheum myART MAGAZINE: Our cover photo for this issue would seem to be the very antithesis of the currently omnipresent selfie photo. In it, you appear superior and have the shutter release at your fingertip. What constitutes an Elfie Semotan photograph when it isn’t a self-portrait?

Elfie Semotan: I think a general orientation is always present, even when you develop in a new direction. It will depend on the genre of course, but that this something isn’t exactly explicit I can say with certainty.

Or as a friend of mine accurately put it: “You photograph things that can’t be seen”. Seemingly useless things, trivialities.

…Or things that you don’t see yet. People continuously learn to see things, new things that they haven’t seen before. To shift focus to things that you normally wouldn’t pay attention to is a universal learning process.

For example, to wildly growing vegetation – as you have done in the works shown recently in a joint exhibition with Michel Würthle, artist and legendary owner of Paris Bar in Berlin. You appear to be, in the positive sense of the word, unpredictable. One might have expected Würthle’s ironic, masculinity-brimming cowboy- and Western-themed drawings to be accompanied by “male gestures”, your wonderful series of photos picturing Shalom Harlow in men’s suits in various masculine poses. But instead – shrubbery!

I couldn’t and wouldn’t want to add anything material to the drawings. It’s does help, however, to know that my photos were shot in the Catskills, an area once inhabited by indians.

Nature, still-lifes, has become an important theme in art and photography in later years…

It has been a theme of mine for ages. Landscapes and wildly growing vegetation were actually the motives in my earliest work. That they have returned now can be ascribed to a personal development, but also to photography in general. Considering what is happening to photography – with selfies, portraits, the immense overload of images – it seems almost natural that we also experience a stronger presence of introspective still-lifes that offer the observer a space for undisturbed reflection.

In your photographs, staging plays an important role, but so does coincidence – as illustrated by your Asphalt series.

I wanted to document the road in Burgenland that leads to my house. It was constantly under repair; surface markings were chopped to pieces and new ones were added. This stretch of road manifested many years of history. The photos were incredibly sentimental, even if they did look rather prosaic.

A quite different aspect of your photography is the work you have done with superstars. Who has made the greatest impression on you over the years?

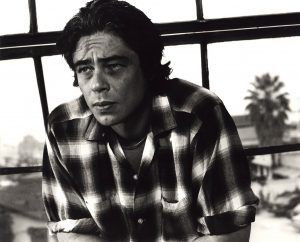

Benicio del Toro. He arrived alone and relaxed to the studio and evidently had no ambition to look great for the occasion. He looked brilliant in his own special way – the aura of unpretentiousness probably makes up much of his attractiveness.

A picture says more than a thousand words?

People interpret pictures in different ways. If I want to explain what I personally see, I rely on words to communicate it. I would never abandon the spoken word in favor of pictures. People always tell me: “Smileys are very important!” I don’t accept that. They are too simplistic and impersonal to convey anything meaningful about the person behind the message. I want to express myself in a more precise manner.

Except for TV-commercials, you have hardly ever worked with moving images. Does cinematography involve too much co-dependence for you to thrive?

You always depend on others. I appreciate Sofia Coppola’s answer in an interview about her film “Lost in Translation”. She didn’t have much money and always brought just two-three people to the set, she said. I often found myself in a similar situation. It gives the work process a certain intensity or density. It’s not always an advantage to have everything at your disposal. Sometimes it kills the spirit and reduces a person’s creative possibilities. A big set-up can be a restraint on individual self-expression.

Quite appropriately, one of the characters in Coppola’s movie says it’s all girls’ dream to become a photographer – eventually, she has only pictures of her own feet to show…

A good observation. It appears easy to become a famous photographer because everything is digital nowadays. I merely have to point my camera at something to shoot a great picture that will change my life. Sure, among the many millions of photos shot there will always be something unexpected. I just don’t think anyone should wait for the unexpected to happen. Instead, you should try to find your personal expression, and that’s something that must be developed. It takes time.

Photography used to also be a means of capturing reality. Today, Photoshop and digital photo manipulation are standard tools. What role does the photograph still have to play in today’s world?

The photograph’s claim to truth is long gone. It’s this same loss of irrefutable truth that Trump exploits when he says everything has been manipulated. It raises the natural question: “Why then should I believe anything you are telling me?” We are left with the choice to pick a few people and institutions that we trust.

Did any particular role-models or artistic influences help shape your sense of aesthetics? Your Lucrezia for example, who tries to kill herself with a painter’s spatula, springs to mind…

Rembrandt and Caravaggio managed to capture people in their paintings that looked more vibrant and alive than any photograph ever taken has. It’s fantastic! Every person portrayed has the perfect facial expression, the lighting is always perfect. This perfection cannot be duplicated with a camera. The painters’ ability to precisely capture the special moment of a situation is something I envy them a great deal.

Do you collect art?

I wouldn’t define myself as an art collector, but I suppose to some degree I am. I collect works by people I know personally and appreciate, such as Martha Jungwirth and Tobias Pils, but also by artists whose works I simply take a particular liking to. That to me is a prerequisite to collecting – the love of beautiful or peculiar things. I collect randomly, not systematically, but I do keep track of what is happening.

The work of your late husband, Martin Kippenberger, is fetching incredible prices at the moment. Has this price level astonished you?

The price level wouldn’t have surprised Martin. He always felt confident about the quality of his work. I did too. But we never discussed prices.

Kurt Kocherscheidt, Martin Kippenberger, Michel Würthle: Your inner circle always consisted of artists. Even Helmut Lang, who wandered from fashion to sculpting, has eventually become an artist…

He always was an artist!

So, you do actually prefer contemporary artists to the old masters?

I prefer to visit old masters in museums. I recently did a photo shoot in Vienna’s Art History Museum for a local fashion company. The owners are friends of mine. I’ve had free hands with their catalogue for years, and this collection was a perfect fit to the old masters. I tried to integrate into the pictures my observations of museum guests. The models were shot as they were taking selfies in front of art works.

“Me and Rubens”, “Me and Breughel”

individuality by the thousands. Is there a viable contraposition to this phenomenon?

Boredom! I miss boredom. It forces you to contemplate. The boring moments in my childhood have etched themselves into my mind, the sounds and landscapes connected with them, the heat. I like boredom. It makes you conscious of yourself and your needs, it pushes you to act – or me it does.

Boredom as engine of creativity?

Absolutely. I lay in bed as a child and studied the pattern of the wallpaper and saw incredibly things, in the folds of my bed linen too. I could spend hours imagining things. Most things in life have a predetermined format. When they don’t, you have to create it yourself. I think that’s good for you.