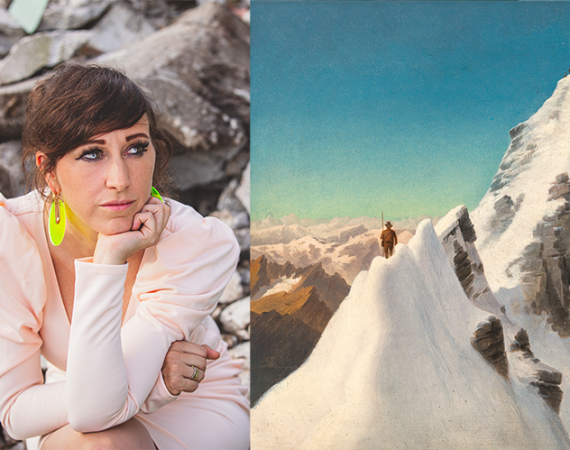

The work of Wiener Werkstätte (WW) and its co-founder Josef Hoffmann is widely known, yet hardly anyone has heard of the women in that collective enterprise. In a long overdue exhibition, Vienna’s Museum for the Applied Arts (MAK) is shining a spotlight on these female artists. Art history would have to be rewritten if their work were taken into consideration say exhibition curator Anne-Katrin Rossberg and Dorotheum’s specialist Magda Pfabigan. A conversation.

their own artistic approach

Magda Pfabigan: The female artists of the Wiener Werkstätte, for example Gudrun Baudisch, Vally Wieselthier and Kitty Rix, regularly achieve high prices at Dorotheum, and yet they feature less prominently on the art market than their male counterparts. The same applies to exhibitions of their work.

Anne-Katrin Rossberg: That is right. The exhibition at the MAK in spring 2021 has long been overdue. In the course of our research for the exhibition, around 180 female artists have been traced, around 130 of whom are illuminated by detailed biographies. They now have names, often also a face, and we know more about their backgrounds and education.

Pfabigan: There are three areas of discussion on the topic of “women’s art”: the legitimate assertion that excluding the female sex from the art business is an injustice; the question of whether women have a different “view of the world”, and whether their representations are based on an alternate paradigm to that of their male counterparts; and finally, the issue of a special perspective, particularly of modern female artists and the Wiener Werkstätte.

Rossberg: The Wiener Werkstätte is a special case. In 1916, Josef Hoffmann and Dagobert Peche created a kind of haven for women artists in this artists’ workshop. Here, women were at liberty to work and experiment freely. Members were individually selected by professors. Artistic creations ranged from Christmas decoration and domestic pottery to original ceramics.

Pfabigan: The women artists created mostly decorative objects, toys, and accessories. These objects were not primarily utilitarian. Does that not contradict the early ideas of the Wiener Werkstätte?

Rossberg: The practical element was of course always there, even with the decorative works which were in fact also being created right from the start. The early ideal of the Wiener Werkstätte was primarily to harmonise material and design. Eventually the artists moved away from this arts-and-crafts concept, especially after Dagobert Peche started working for the WW in 1911. He steered a decorative, playful course which greatly influenced the women artists.

Pfabigan: The art of Dagobert Peche includes many “feminine” characteristics in its ornamental language. I think that every female WW artist had her own artistic approach. For example, the modernistic creations of Vally Wieselthier were more reminiscent of Modigliani than of Klimt or Schiele. But in addition to aspects of playfulness, the women could also create objects of great seriousness and severity, as demonstrated by Gudrun Baudisch’s heads.

Rossberg: Yes, art history should, in fact, be rewritten as a result of these diverse new findings.

Pfabigan: And who would have thought that a Rococo revival reflecting a skilful nonchalance and erotic adventurism would be celebrated in Vienna around the time of the First World War?

Rossberg: That was one aspect of the time. However, there was also a constructive, functional, geometrical orientation very early on: for instance, Maria Likarz set new standards in 1910, even before emergence of the Bauhaus, with her pioneering “Irland” fabric design. In general, there were some very early developments in Vienna that anticipated both the Bauhaus and Art Déco.

Pfabigan: After the First World War, these WW artists reacted to global events with a discernible detachment from the world and pursued a carefree, even playful direction.

Rossberg: Exactly. Most WW women felt their responsibility lay elsewhere; they were not politically motivated. However, there were also some who made their own statement through their membership of movements such as the Austrian Werkbund or the association of women artists, the Wiener Frauenkunst.

Pfabigan: If we use the term “female Secession” in the context of Wieselthier’s portrayals of women, we encounter some complex characters. They are in the process of “doing” something, that is to say, in the process of an activity, but they are also undeniably ladylike and thoughtful at the same time.

Rossberg: The women of the WW also experimented with new gender roles and social norms, for example, they appeared with a pixie haircut and in male clothes. The issue of smoking was also significant, both as an act of emancipation and with regard to new products: they designed ash trays, cigarette cases and matchboxes to be used by women.

Pfabigan: The elegant head postures of the mask-like sculptures made by Gudrun Baudisch also reflect this tendency. Sometimes the eyes are closed. The question is, why? Whether with open or with closed eyes, it is clear that a new era was dawning on the work of the Wiener Werkstätte, their production methods and their understanding of the sexes. The use of expressive glaze really did create something unique. It was not about an ideal, but about a different, new form of language which emerged from a philosophical background.

find out more about the Wiener Werkstätte

EXHIBITION

Women Artists of the Wiener Werkstätte

21 April 2021 – 3 October 2021

MAK – Museum of Applied Arts