Antiquity and Old Masters, Napoleon’s war horse, Neymar the fallen warrior … Martha Jungwirth’s painting, which she calls seismographic, encompasses all that and much more. And yet it would seem these things are little more than

a “pretext”. Hans-Peter Wipplinger visited the eminent contemporary artist in her studio.

Hans-Peter Wipplinger: Dear Ms Jungwirth, dear Martha, you recently had a solo presentation at Arco Madrid. Which of your works were on display?

Martha Jungwirth: Einige Arbeiten aus der Serie „Vladimir Nabokov: Erinnerung, sprich“, zu denen mich eine Reise nach St. Petersburg 2017 inspiriert hat. Dann Auszüge aus meinem „Corona-Tagebuch“ – kleine, bemalte Kartons, die einmal als Rückwände von Bilderrahmen gedient und eine gewisse Schäbigkeit haben. Auf denen habe ich mich durch die Pandemie gearbeitet, meine täglichen Notationen zu diesem ganzen Irrsinn festgehalten. Und dann meine drei „Majas“, das hat mich ganz besonders gefreut! Gern wäre ich nach Madrid gereist, um sie dort zu sehen und um Goyas Gemälde im Prado zu besuchen, wo sie nach der Ausstellung in der Fondation Beyeler bei Basel neu gehängt wurden, zusammen mit Titians Venus – das muss fantastisch sein!

Martha Jungwirth: A couple of works from the “Vladimir Nabokov: Speak, Memory” series, which I was inspired to paint on a trip to Saint Petersburg in 2017. It also included extracts from my “Corona Diary” – which is to say small, painted, somewhat shabby paperboards that I initially used as backing for picture frames. I used them to work my way through the pandemic and make my daily notations on all this madness. I also showed my three “Majas” in Madrid, and that was really, really delightful. I would have loved to travel to Madrid to see them, and see Goya’s paintings at the Prado. They were out on loan for a show at Fondation Beyeler near Basel and have now been rehung alongside Titian’s “Venus” – what a fantastic sight that must be!

Goya wasn’t the first “Old Master” to inspire you to do a series of works, was he?

No, not at all (laughs). Frans Hals is another one, with his “Regents of the Old Men’s Almshouse”. There’s also Cranach’s “Judith with the Head of Holofernes”, which is now on view at the Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien. I’m interested in the way artists perceived the world in the old days, the things that preoccupied them, how they approached painting. That is what inspires me. Did you see the Chaïm Soutine and Willem de Kooning show at the Musée de l’Orangerie? I was in Paris before Christmas, and I absolutely loved it. American Abstract Expressionism was extremely important to us in the 1950s, but Austria also had Richard Gerstl in the early 20th century: the radicality and modernity of his work was unheard-of in painting at the time – it was fantastic! Gerstel passed away when de Kooning was still in short trousers.

Courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac London · Paris · Salzburg · Seoul,

© Martha Jungwirth / Bildrecht, Wien 2022, Photo: Ulrich Ghezzi

Gerstl has no doubt inspired artists to this day, from Günter Brus to Arnulf Rainer, Georg Baselitz and Paul McCarthy. Six of your wonderful interpretations of Gerstl’s double portrait of the Fey Sisters were shown in our 2019 exhibition “Richard Gerstl” at Leopold Museum, right next to his paintings. But your works address current events as well. I’m thinking of the 2017 “Istanbul” series, for example, which alludes to the suppression of the attempted coup in Turkey. I can tell from the constantly refreshed crop of newspaper clippings pinned to your studio wall that you’re an avid reader of “Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung”. Isn’t that Bayern goalkeeper Manuel Neuer planting himself in front of an onrushing goal-getter, arms and legs outstretched to

block the ball?

Exactly. And right under it, I hung Guido Reni’s rendering of the race between Atalanta and Hippomenes. It’s a different scene, but I was interested in the similarity of expression and the dynamic gestures, even if their goals are entirely different: one of them wants the cup, while the other wants the bride. Here’s another footballer (reads the caption), Neymar.

He’s a striker on the Brazilian national team; he plays for Paris Saint-Germain as well.

I see. He immediately reminded me of the fallen warrior on the pediment of the Temple of Aphaia in Greece. (fishes out a “Du” culture magazine from the 1950s) Look at him here! It’s a wonderful black-and-white photograph, and the artwork in these old magazines is marvellous too.

The analogy reminds me of Aby Warburg’s “pathos formula”: he regarded memory as humanity’s “treasure chest of woe”. The passion in facial expressions, a heightened expression of sign language … Warburg analysed how a specific set of forms was handed down from antiquity to the Renaissance and Modernism. What is that beneath the fallen footballer Neymar?

That is Napoleon’s sarcophagus. You can see it here (points to another newspaper clipping). Above it hangs the skeleton of his horse, Marengo – not the real one, obviously, but Pascal Convert’s replica of it, made for the 200th anniversary of Napoleon’s death. The horse carried Napoleon all the way to the Wagram ridge in Lower Austria, and even to Waterloo, where it was eventually captured and used as a stallion by the English.

© Martha Jungwirth / Bildrecht, Wien 2022, Photo: Lisa Rastl

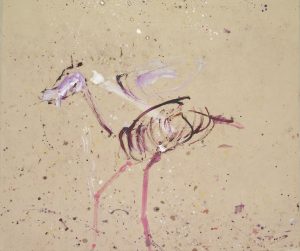

What a story! Didn’t you also paint a “portrait” of Marengo? I seem to recall that your first exhibition with Thaddaeus Ropac in late summer last year featured an eponymous picture.

That is correct. I actually deployed a whole menagerie in Paris:

a dog, a monkey, a toad …

… and “La Grande Armée”, your main work, more than seven metres long; it was very impressive. It features three animals lined up and stoically striding from left to right across the canvas. They are silhouettes, very reduced yet also very powerful, painted with expressive, sweeping brushstrokes.

They are animal figures similar to those found in Tutankhamun’s tomb. You can see them here on a photo Harry Burton took right after the tomb was opened: royal animals amidst all those stools, chests, and wheels of war chariots. They are death beds in animal form – magnificent artefacts!

The Paris show also featured triptychs, or “battle pictures”, if I may call them that, and a series of smaller works which you titled “Metopes”. The term is more common in architectural history. How are these two groups of works related?

They were both created at a time when I was very much into Homer’s “Iliad”. As you know, I’m very fond of Greece, not just the landscapes and people, but Greek mythology in particular. I stumbled upon a book by Alice Oswald, “46 Minutes in the Life of the Dawn”, and in it I found the poem “Memorial: An Excavation of the Iliad”, which moved me deeply. All the warriors, victims of battles, the dying, get a chance to speak. So I guess in that sense the two triptychs I called “Memorial” are indeed battle pictures. “Metopes” were originally figural decorative bands in Greek temple friezes; I like to call them “cartoons”: they are small narratives within the bigger whole, fields in which I release all my painterly energy whenever I’m lost for ideas in the larger surface. I do occasionally have my own internal struggles and battles after all (laughs).

from the “Cambodia” series, 2005

watercolour on paper, 137 x 101 cm

sold at Dorotheum

You mentioned the Greek landscape. Apart from the

Cyclades, whose natural atmospheres you captured in numerous watercolours, your travel destinations have also included Istria, Yemen, Cambodia and Bali. Did you paint in all those places?

At the beginning I did, yes. I painted en plein air. I felt like Cézanne (laughs)! For example, in Rome, I sat on a stool in front of Santa Maria della Pace with my watercolours and a bottle of water, and I painted the Baroque façade. That was back in the 1970s, ages ago. Today, I only paint from memory, particularly now that carefree travel is a thing of the past. I currently draw my inspiration from more obvious motifs, like a bouquet of wilted flowers, a cloak hanger, or my little painting table. Even the yellow, wooden boards of the shelves holding my paintings have become worthy of a painting, which I call “Corona Prison”.

But these objects are no longer recognisable as such in your paintings

No, they are only a pretext. Something about them sets off a spark, a particular shape or colour that gets me going visually. But it can only become a painting after the motif has gone through me emotionally, once it has triggered something in me and moved me, also physically.

You once described your art as “seismographic”.

Yes, and the dynamic interplay between my internal and external movements is what sets the brush in motion.

What are you currently working on?

I’m working on paintings for a solo exhibition at Thaddaeus Ropac’s London gallery later this year and a major retrospective at Kunsthalle Düsseldorf in the autumn. I’m hoping to get a few things done by then. Chance and spontaneity are constant companions on the job; they co-define the painted result, along with ratio. So, my work is also always an experimental venture into new realms.

Thank you for your time, and all the best for your upcoming projects!

The interviewer, Hans-Peter Wipplinger, is Director of the Leopold Museum in Vienna. He was head of Kunsthalle Krems until 2015, where he curated the 2014 exhibition “Martha Jungwirth. Retrospective”.

Martha Jungwirth

Born in Vienna in 1940, she occupies a singular position

in contemporary Austrian painting with her poetic-

abstract watercolours and oil paintings. After her studies at the University of Applied Arts (and three awards, including the Msgr. Otto Mauer Prize),

Jungwirth took part in the legendary 1968 exhibition curated by Otto Breicha in the Vienna Secession, as part of the collective “Wirklichkeiten” (Realities), which continued to exist until 1972. After participating in documenta 6 in 1977, the artist withdrew from the public spotlight. In 2010, painter-curator Albert Oehlen chose Jungwirth’s work for a group exhibition at the Essl Museum. In 2014, the Kunsthalle Krems dedicated a personal exhibition to her, covering five decades of her work. Solo shows followed in 2018, including in the Albertina, Vienna, and in the Ravensburg Art Museum. In the same year, Jungwirth received the Oskar Kokoschka Prize, and in 2021

the Grand Austrian State Prize. A solo exhibition is scheduled at Kunsthalle Düsseldorf later this year.