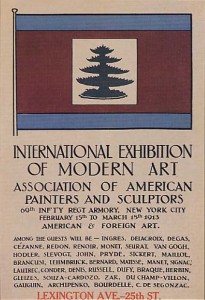

103 years ago in February saw a significant turning point in the history of modern art and, according to some, the integrity of American morality. The Armory Show of 1913, whose name the modern-day art fair pays homage to, was the first exhibition in the United States to feature the European avant-garde of Fauvists, Cubists and Futurísts.

America is today a byword for modernity, unabashed confidence and tolerance. A superpower as much culturally as economically and militarily, the United States is very much at the forefront of radical and modern art. Yet in the early 20th century it was the Old World setting new and scandalous artistic trends incarnated by the likes of Picasso, Matisse, Duchamp, and the Secession while across the pond gilded age realists like Singer Sargent still held sway and Vanderbilts had barely stopped reconstructing imported French châteaux on Rhode Island .

Yet from February 17th to March 15th after assiduous planning, works by Picasso, Matisse, Duchamp, Gauguin, Cézanne, Van Gogh and Monet among others found themselves being displayed for the viewing pleasure (or in many cases displeasure) of the American public. Walter Kuhn, the painter and executive organiser of the show, had in 1912 undertaken a tour of Europe with the purpose of acquiring key examples of European modernism from the continent’s most forward-thinking artists. While many American artists like Kuhn had spent considerable time in Europe as part of their artistic education, to the American public at large modernism was unfamiliar and radical. Indeed during the planning of the show in 1912 Kuhn had pronounced “We will show New York something they never dreamed of”. It seems he succeeded in this aim.

The prime offender

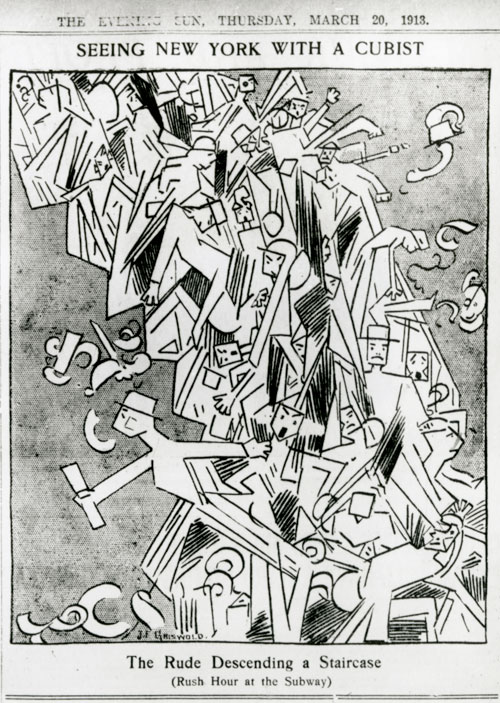

The contents of the show (namely those by European artists) immediately scandalised the city and the public, with particular vitriol directed against Marcel Duchamp’s Nude descending a staircase. The artwork, which had been rejected by the Parisian cubists as being too futurist, inspired ridicule and mockery amongst the denizens of New York. The successive superimposition of images to depict motion descending a staircase found itself satirised in the New York Evening Sun as the “The Rude descending a staircase (Rush-hour at the subway)”.

Yet the most scathing analysis of the painting was surely from former President Theodore Roosevelt. Having visited the show, Roosevelt wrote a critique of the art he had seen, interestingly and perhaps not all too objectively reserving praise for the American art on display and excusing the “acknowledged masters’ Monet and Cézanne, while heaping disdain on the other European works and in particular our favourite Duchamp. A rather witty comparison sees Roosevelt savage Duchamp’s masterpiece in favour of a Navajo rug in his bathroom: ‘There is in my bath-room a really good Navajo rug which, on any proper interpretation of the Cubist theory, is a far more satisfactory and decorative picture”. The former president went on to say that cubism is to art what nonsense-rhymes are to literature. Yet for all this criticism the Armory Show was a huge triumph, slowing the march of American post-impressionist realism and introducing modernism to a nation where it is now taken for granted as a key contingent of artistic heritage.

The show must go on

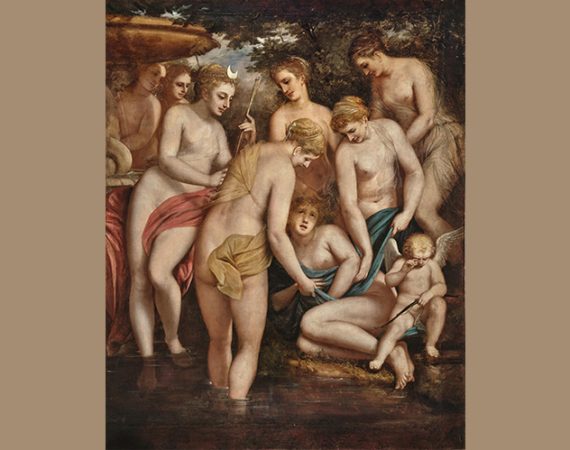

Another source of controversy was Matisse’s Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra). Having shocked the French public 6 years before, this Fauvist work, reputedly a motivation for Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, faced accusations of moral flagrancy and calls for censorship along with the cubist works. When the Armory Show moved to Chicago, ironically a city now seen as a bellwether for progressive culture and politics, students gathered to burn effigies of Matisse’s painting and the following headlines could be seen in local newspapers: Cubist Art Will be Investigated; Illinois Legislative Investigators to Probe the Moral Tone of the Much Touted Art (Ottumwa Tri-Weekly Courier, Iowa, 3 April 1913).

Judging from his early turn-of-the-century moral compass we can safely assume that cubism would be the least of Theodore Roosevelt’s worries in regard to today’s morality. Perhaps most telling of the success of the Armory Show is the fact that while Roosevelt’s like-minded friends over at the Ottumwa Courier are these days producing such catchy headlines as “Higher Camping Fees at Ottumwa Park Coming April 1st” (February 2016), Picassos are selling at up to $175 million and not far from the birthplace of American statehood hangs Nude descending a Staircase in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.