DOROTHEUM SELLS DRAWING BY SCHIELE “Reclining Woman” FOR €2.3 MILLION

Highest price paid at auction in Austria in 2017 to date

Egon Schiele was one of the most eminent and radical draughtsmen of the 20th century. He elevated drawing to an independent art form. Two of his works, in private ownership for 85 years, will be auctioned at Dorotheum in November.

28 October 2018 marks the centenary of Egon Schiele’s death. Dorotheum is already honouring Schiele this year by offering at the Modern Art auction two outstanding drawings by this great protagonist of the Wiener Moderne, which have been in private hands for more than 85 years.

Egon Schiele

1917 was one of the most prolific years in Schiele’s artistic life. In spite of the war and his duties as a soldier guarding Russian prisoners of war, Schiele was able to pursue his art and take part in international exhibitions. He and Albert Paris Gütersloh were finally commissioned to organise the 1917 war exhibition at the Vienna Prater.

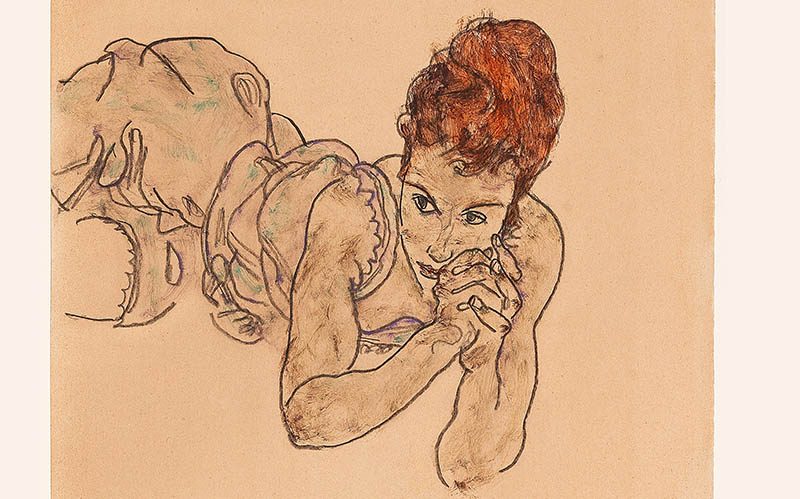

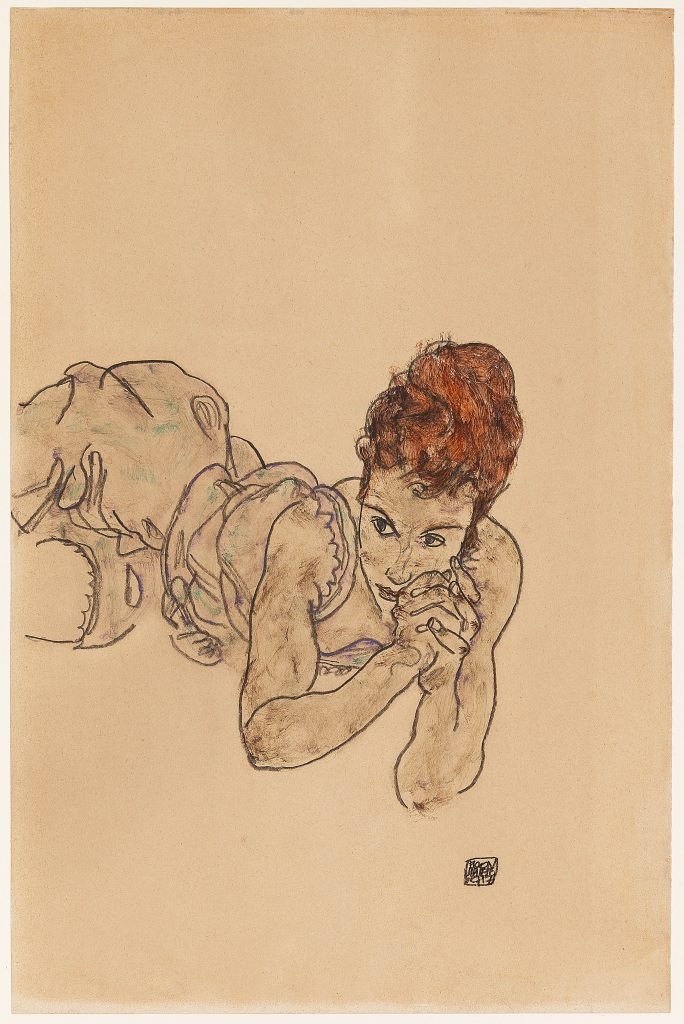

At the same time he created numerous portraits and nudes, including of his wife Edith and her older sister Adele. One of these nudes is “Reclining Woman” from 1917, which features in the Modern and Contemporary Art auction in November. We can only speculate whether Adele is the woman in the drawing. Without a doubt, however, the drawing of “Reclining Woman” shows how Schiele turned his back on conventions and broke new ground in terms of content and form.

French protagonists of nude painting such as Edgar Degas or Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec suggested that the artist was a hidden observer, watching models as they went about their daily business, bathing, undressing or sleeping. Egon Schiele abandoned this approach, removing his models from any spatial environment. Even Gustav Klimt showed his models as beings indulging their sexuality, their closed eyes seeming not to notice the artist.

The erotic nude as an autonomous work of art

Schiele’s “Reclining Woman,” on the other hand, presents herself to the viewer, displaying the active relationship between artist and model. The role of observer is consciously included, the process of observation becomes a topic in its own right. Like all of Schiele’s illustrations of women, “Reclining Woman” is a deliberate staging of body and sexuality: the artist made eroticism the object of the picture and thereby elevated the erotic nude, which had been more of a study in previous art history, to an autonomous work of art.

The formal aspect is also fascinating: a refined play of lines, subtle foreshortenings and overlaps, and Schiele’s way of directing the gaze, which sometimes goes beyond the limits of the paper.

A key figure in European drawing

Schiele is rightly viewed as one of the most important and radical draughtsmen of the century – not least by the great collector and Schiele expert Rudolf Leopold: “The visual tool that Schiele created and that demonstrates his artistic originality, in fact mastery, was his personal line. He also mastered the art of emphasis and omission. More than any other graphic artist, Schiele managed to convey both shapes and emotions with mere drawings, often using nothing but outlines. Without question Schiele as a draughtsman holds a unique position within Expressionism. Nobody else has created lines in such a masterly and expressive way: sharply rigid or supple, constructive or fragile, brittle, nervous, scrawled or tense, intermittent or strident.”

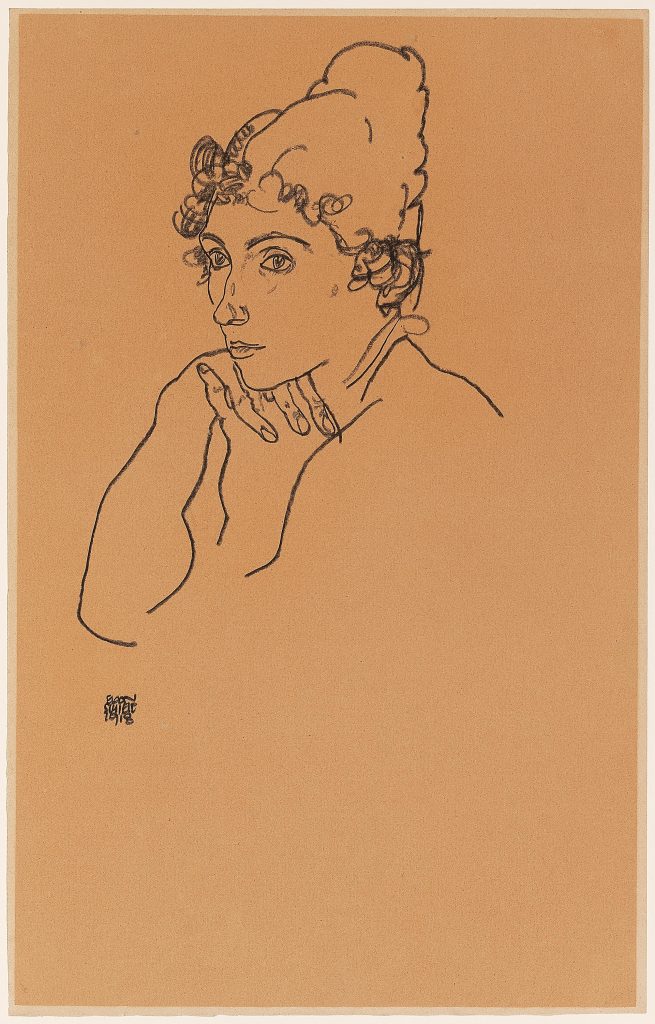

Head of a woman

Another item in the auction, “Head of a Woman,” from the same collection, is an example of how Schiele managed to capture emotions with a few lines, through emphasis and omission.

This portrait of a woman is dated 1918. In that year Schiele planned to found a Kunsthalle similar to the Secession together with Gustav Klimt, Josef Hoffmann, Arnold Schönberg, Anton Hanak and Altenberg. However, the project failed due to a lack of funding. Gustav Klimt died on 6 February 1918.

Schiele’s big break

Schiele’s breakthrough and greatest financial success was the Vienna Secession exhibition that same year. The Austrian Gallery in the Belvedere purchased the painting entitled “Edith Schiele, Seated,” the first and only time a museum purchased a Schiele work during the artist’s lifetime. Schiele’s works now began to be admired and sought after by many collectors. Schiele was able to rent another studio and intended to found an art school, making plans for example for a special Sonderbund with a branch in Vienna’s first district, for new exhibitions, and plans to equip a mausoleum with paintings on the subjects of “religion, the cosmic concept, life struggles, death, resurrection, and eternal life.”

The outbreak of the Spanish flu in Vienna in the last days of the war put an end to all his plans. Edit Schiele died on 28 October; just three days later, at only 28 years of age, Egon Schiele too succumbed to the illness.

1918 brought not just the downfall of the Danube Monarchy and the end of the old world order. The death of Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, Kolo Moser and Otto Wagner also put an end to a seminal period of Austrian art history.

Information: Elke Königseder, specialist for modern and contemporary art