Mark Rothko is arguably one of the most sought-after artists of our time. His large paintings regularly fetch over $30M at auction, with a world record of $86M in 2012 for the colourful “Orange, Red, Yellow” (1961).

As a retrospective exhibition opens at the Kunsthistorisches in Vienna, Christopher Rothko, son of the artist, head of the estate with his sister Kate and chair of the Rothko Chapel in Houston, publishes a German version of his book “Mark Rothko: From the Inside Out”, to tell us why we got it all wrong.

______

by Maïa Morgensztern

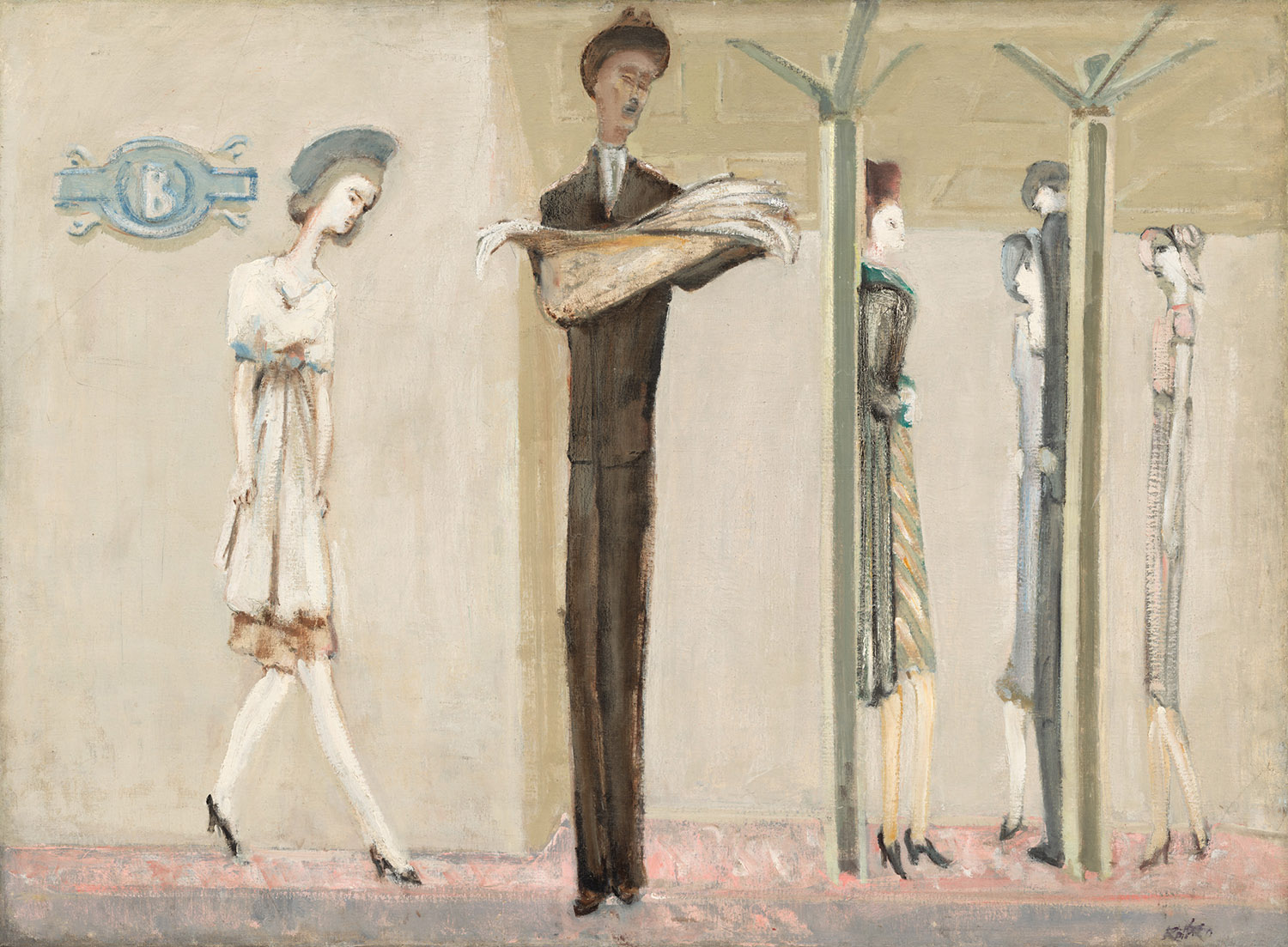

Maïa Morgensztern: Mark Rothko spent over twenty years doing figurative work, experimenting with different styles along the way. Despite the apparent variations, he was always primarily interested in revealing ‘the state’ of his characters, rather than depicting a physical reality. Can the same be told about his abstract works?

Christopher Rothko: Absolutely. You can look at a figurative sketch from the 1930s or a more surrealist work from the 40s; they all seem very different from what we think of as a Rothko. But he is not necessarily trying to show you what you would see. It’s a much more internal view. Rothko is basically interested in starting a conversation with you via his art, hoping that you will bring your perspective, filling in all the gaps he has intentionally left. He’s giving you a suggestion and you have to complete it, whether it’s a figurative piece or the most abstract painting.

In 1958, Rothko gave up figurative works, arguing they “did not meet [his] needs” and switched to abstraction. What was he looking for at that time?

To me, his last works of full-fledged figuration, in 1938–1939, are some of the best he ever made. At that point he was almost more interested in the spatial elements and their relationships with one another than in the figures themselves. He stripped everything away to reach the essential, almost strictly dealing with form rather than colour. It then took a decade of so many changes for him to get there, in 1949.

This idea of the supremacy of forms, or ‘measures’ as Rothko defined them, seems quite against the general belief that Rothko’s works are all about colour …

Colour is certainly an important part of Rothko’s language, but it is a sort of first seducer, if you will. With the exception of some mural studies, none of his sketches for his classic abstract paintings are in colour. They are first approached through pen and ink. These sketches give us an inside-out perspective. They are the bones of the work. So Rothko is not thinking through colour, as one might think. Looking at my father’s practice over the years, the question of form has always been prevalent. From the beginning, the forms frame the experience. As Rothko goes through the 50s and into the 60s, the paintings keep on getting wider and almost fully envelop us, demanding our full attention. These soft fuzzy rectangles of the classic era are essentially our field of vision. Rothko is showing you what you already see. Ultimately, the paintings are not about who he is. They are about Rothko’s idea of what it means to be alive.

_________

Maïa Morgensztern is BFAMI Head of Cultural Programme and Editor in Chief of CULTURE ALT.com

“Mark Rothko” is on view at the Kunsthistorisches Museum until June 30, 2019. Christopher Rothko, “Mark Rothko: From the Inside Out” (Yale Press) is now available in German under “Mark Rothko: Dramaturg der Form” (Piet Meyer Verlag, Kapitale Bibliothek)