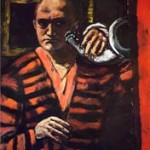

Not everyone’s born smiling! Born 132 years ago this February, Max Beckmann’s self-portrait of 1918 proves sunny dispositions are overrated.

This self-portrait captures the artist at a critical moment in his career, torn between his devotion to figurative painting and his desire to express the disfiguration he had witnessed in World War I.

Anything but a model soldier, Beckmann didn’t fire a single shot in battle. “I refuse to shoot at the French,” he said, “because they have taught me too much. Nor can I shoot at the Russians, because I love Dostoyevsky.” Beckmann found the answer to his dilemma not in Expressionism, which he saw as melodramatic navel-gazing, but in the distorted figures and medievalesque composition of New Objectivity (to borrow a phrase, no one could bend it quite like Beckmann). Beckmann himself called his style transcendental objectivity. And why not? The allegories for human tragedy and sharp social criticism that mark his mature work are profound enough to transcend even Beckmann’s signature scowl.

We know Valentine’s day was last week but we can’t resist a love story – especially one that began in our home city and went on to inspire heaps of wonderful art! Beckmann met the 19-year-old violinist, singer and actress Mathilde “Quappi” Kaulbach in Vienna in 1924. By 1925, he had divorced his wife Minna and married Quappi. She set aside her musical ambitions to further his career, forging relations with curators, collectors and patrons. Beckmann painted countless portraits of her over their 25-year marriage. Like any love, theirs had its good and bad days; Beckmann’s last diary entry before his death in 1950 read only “Quappi’s angry.” But the two were inseparable. “He completely indulged me,” Quappi wrote in her 1983 memoirs “My Life With Max Beckmann.”

Happy birthday, Max! Thanks for all the beauty.