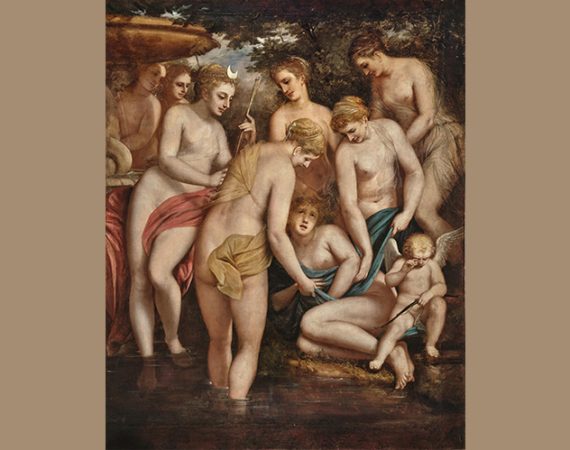

The female artists of the 17th century are currently gaining the acclaim and recognition they deserve: paintings by Fede Galizia, Artemisia Gentileschi and Orsola Maddalena Caccia illustrate their skill and the quality of their work in the Old Master Paintings sale in May 2023.

The invisibility of the female artists in a history of art largely recorded in male terms, is currently undergoing a complete revolution. The work of female artists is increasingly being studied and brought to the attention of the public through exhibitions and publications and is leading to a considerable growth in interest. It was naturally not lack of skill that has led female painters to be overlooked in the passage of art history, but rather the systemic lack of opportunity available to them which is to blame for the small number of female “old master painters” we have heard of. Are we finally witnessing the recognition of the “old mistress painter”?

Women artists have been documented since antiquity, however, it was only with the spread of humanist ideals during the Renaissance, that a larger number of women were able to enter the male-dominated business of art production. As female painters were denied access to the great workshops, their artistic possibilities were limited. Therefore, the great majority of women painters in the 16th and 17th centuries came from artist’s families where they had access to materials and education, and their output remained for the large part within the confines of their family workshops.

The careers of the great female artists Fede Galizia, Artemisia Gentileschi and Orsola Maddalena Caccia, whose work is represented in the Old Master Paintings sale at Dorotheum on 3 May 2023, are a case in point.

Fede Galizia (1578–1630) was the daughter of the Milanese miniaturist Nunzio Galizia. She was educated by her father and had already established an international reputation before she was twenty years old. She is noted as a pioneer in the treatment of still- life painting and is increasingly recognised for her portraiture and religious paintings. During her career she repeatedly returned to the biblical subject of Judith and Holofernes. The story is particularly pertinent in the discussion of this female artist’s work as the subject alludes to the apotheosis of a woman’s struggle to impose herself in a male dominated world: in Galizia’s case, the world of art production.

Comparing Fede Galizia’s painting to Bartolomeo Mendozzi’s (circa 1600–after 1644?) work of the same subject, the difference between the male and female artist’s point of view is evident: the centre of Mendozzi’s composition is occupied by the suffering Holofernes who focusses on the spectator as if appealing for help. Judith is depicted as a violent murderer – a femme fatale, her neu- tral, almost absent gaze wandering out into the viewer’s space. In Galizia’s painting, Judith is portrayed as decisive and strong shortly after the moment of action. Her feminine beauty is presented as an expression of virtue, contrasting shockingly with the decapitated head of Holofernes she holds in her hand.

The career of another of the great female artists of the 17th century, Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–after 1654), also began with training from her father, Orazio Gentileschi, who was one of the earliest followers of Caravaggio. As she was not permitted to leave her home unaccompanied, it was difficult for her to study artworks in public spaces, so she began her career copying her father’s compositions and engravings of the work of other artists. Through her talent and hard work however, by the time she was in her early twenties Gentileschi had established her own workshop, employing numerous assistants, even becoming a member of the Accademia del Disegno in as early as 1616. To navigate the patriarchal patronage system, she copied the practice of her contemporary male counterparts and employed agents promoting her reputation across Europe.

Orsola Maddalena Caccia (1596–1676), the daughter of Mannerist painter Guglielmo Caccia, called “il Moncalvo”, also started to learn from her father at an early age. As Guglielmo received many significant commissions, he valued his daughter’s talent and acknowledged her importance in the family workshop. Theodra, as she was originally called, joined the Ursuline order and entered into the convent of Bianzé and later of Moncalvo, becoming Sister Orsola Maddalena and continued her work as an independent artist. She created a flourishing workshop within the convent’s walls, developing an individual style which was popular among her patrons.

Vera Hinteregger is an art historian and cataloguer in the Old Master Paintings department at Dorotheum.

AUCTION

Old Master Paintings, 3 May 2023, 6 pm

Palais Dorotheum, Dorotheergasse 17, 1010 Vienna

oldmasters@dorotheum.com

Tel. +43-1-515 60-403