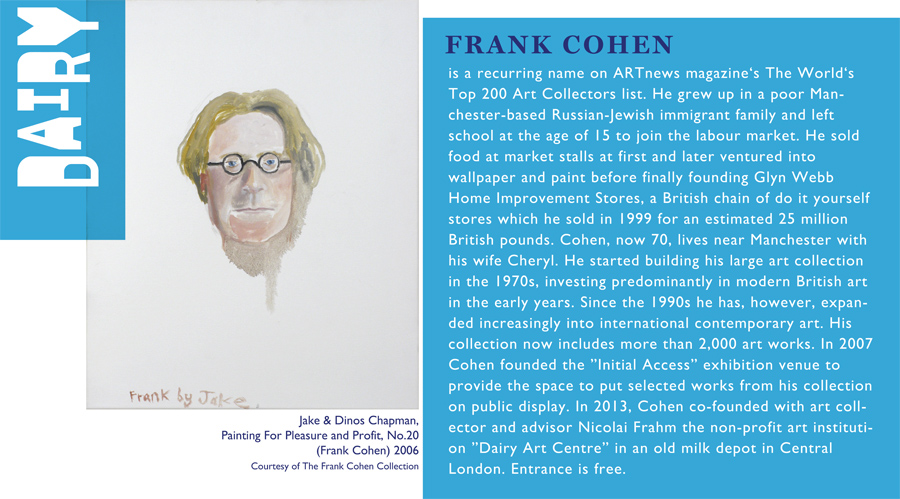

My kind of collecting derives from my childhood – as a kid I collected cigarette cards with footballers or boxers, then rare patterned coins – those designed for the mint. When I met my wife Cheryl in the seventies, her father was an art dealer in Manchester, and I bought limited editions of prints from him. But prints are a waste of time, they’re mass products, so I went on to buying originals.

A painting called Our Family. I bought it for £1,100 pounds sterling from an art dealer in Manchester. It was the size of a postcard and by L.S. Lowry, the English industrial artist. And I went on from there.

Cigarette cards were finished, coins were finished, and I ended up in the art world. And it was like a bug. It just never stopped from then on. I never stopped reading about art. I have no formal education, never studied any history of art, have no BA or MA. I was in the home improvement business: bathrooms, kitchens, carpets. In the old days they called this DIY – ‘do it yourself’.

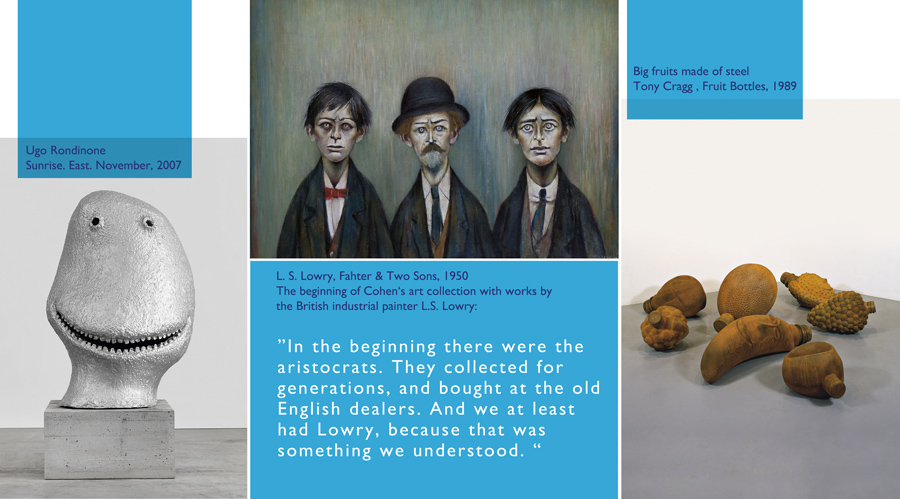

f.l.t.r. Ugo Rondinone, Sunrise. East.November, 2017 | L.S. Lowry, Father & Two Sons, 950 | Tony Cragg, Fruit Bottles, 1989

Well, in the beginning I used to buy art that reflected what I sold in my stores; for example Arman. I used to look at household products that resembled artworks – made using materials that you could actually buy at a DIY store.

In the beginning there were the aristocrats. They collected for generations, and bought at the old English dealers. And we at least had Lowry, because that was something we understood. Once you try to break down the barriers – and I used to go to London, to squeeze my way in – they wouldn’t talk to you. They’d look at the way you were dressed, and if you were wearing a pair of jeans and a T-shirt they thought you must be an idiot, forget it. You needed a pinstripe suit and a tie to be taken seriously. But today it’s all changed: someone walks in with a T-shirt and a pair of sneakers, and they’re the ones who are spending the money. The ones with the pinstripe suits and ties are the ones with no money. It’s gone full circle, into a hip hop world.

There’s more money around, and especially in London. People are coming in from Russia, from China, from South America, from Paris. Everyone wants to live in England because of the very good tax rates. The property prices have gone up like mad. The art market has gone bananas, because all the big galleries are in London. That includes the modern-day dealers who are based in America, maybe also Zurich, such as Gagosian, Hauser & Wirth, Pace, Gladstone. So the art world has completely changed.

It’s all about money today, it is not about the bloody art, that’s the problem. Melanie Gerlis wrote a book called Art as an investment? A survey of comparative assets. Don Thompson’s The Supermodel and the Brillo Box is also very interesting. If you read them it’s clear – it’s all about money. Not that people don’t like art, but they treat it as a luxury good, it’s like money to them. They used to play the stock market, but nowadays they can’t make the same returns. And alternative investments have also become a bit weak.

Of course, but I think the type of art I still buy is no longer the same as that bought by these speculative collectors, the ones now buying Warhols, and Stingels and Christopher Wools. The prices have gone mad. I bought a Wool for US$50,000 not long ago, in 2004, and now even a mediocre Christopher Wool would fetch US$1.5 million! When I bought them, I was never thinking about all that money. My modern British art is a steady market. You don’t sell it, you want to look at it. But even this market is starting to move, because people are getting more interested in art from different countries. Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, David Hockney, really serious British artists – these boys are moving fast in the marketplace.

He’s doing what nobody else is doing. He is fabricating mass-kitsch, everyday household products, blowing them up. It takes years to produce. It’s not everyone who can buy them, because there are not many people willing to wait seven years for an artwork. It’s a kick because they are amazing, look at Popeye, for example. The ones I like are ones which remind me of what I used to like when I was a kid. It’s a play on childhood, a play on everything.

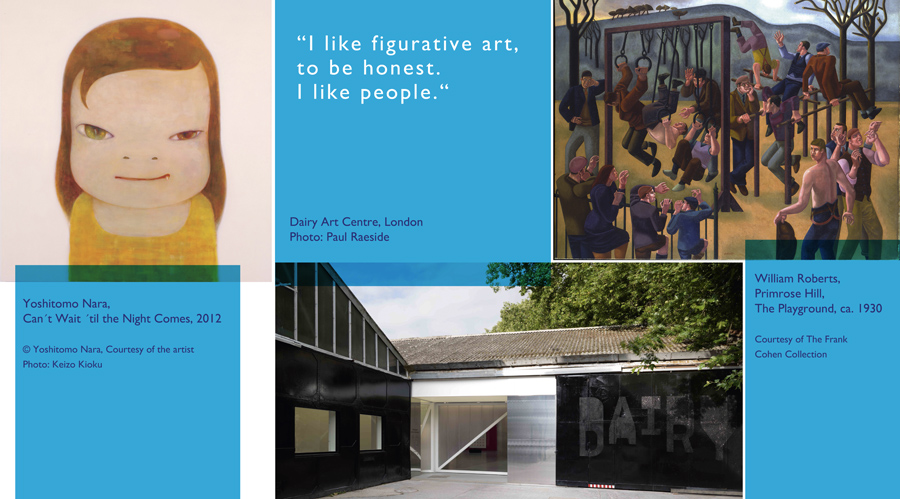

I like figurative art, to be honest. I like people.

For example, work by artists such as Thomas Schütte, Paula Rego, and William Roberts – a wonderful British artist who was most underrated, but who is now becoming very popular.

My partner, Nicolai Frahm, and I didn’t want to show too much of my collection, we thought that would be too ‘in your face’. We’ve done that before in Wolverhampton, at the gallery called “Initial Access”.

We wanted to make it easier to curate, and for it to make more sense. We started with John Armleder, a Swiss artist who was big in the ‘80s. If he were American he’d be ten times more expensive. Our next great show will be Nara! Our advantage is that we can do everything spontaneously, whereas big museums have to plan years in advance.

I think it’s the best place in London, because it has an industrial feel instead of being a white cube, and is not as clean cut as galleries. We have an educational programme, and people love it. We bring back things that London hasn’t had, except at the Tate Modern and Royal Academy. It’s also different from the place Charles Saatchi runs.

I’m friendly with Charles, always have been. He was an innovator in his time, now it’s a different game. His gallery is a very expensive place to run. He’s doing something completely different. It’s like chalk and cheese, if you know what I mean.

The Richard Hamilton retrospective. To me it was the best of British artists brought together, and that makes me think British art hasn’t disappeared out of the window. You can’t buy Hamilton, you never see him. I was really fascinated. I’ve seen hundreds of good shows, Picasso, Basquiat, they are great technicians. But Hamilton – there’s a bit more blood and guts to him.

The older you get, the less bulk you want. If I had a few Hamiltons, and a few Schüttes – I love Thomas Schütte! – as well as a Picasso, a Bacon, maybe a Rothko, a Jackson Pollock, then I would stick to them and not worry about the others.

You want to downsize rather than to upsize. It brings problems: when you die, you have to leave it to your children, to museums… Less is more, and I think that’s where I’m headed now: only masterpieces! But I still look at young artists and buy them. You’ve got to keep your nose in the water…