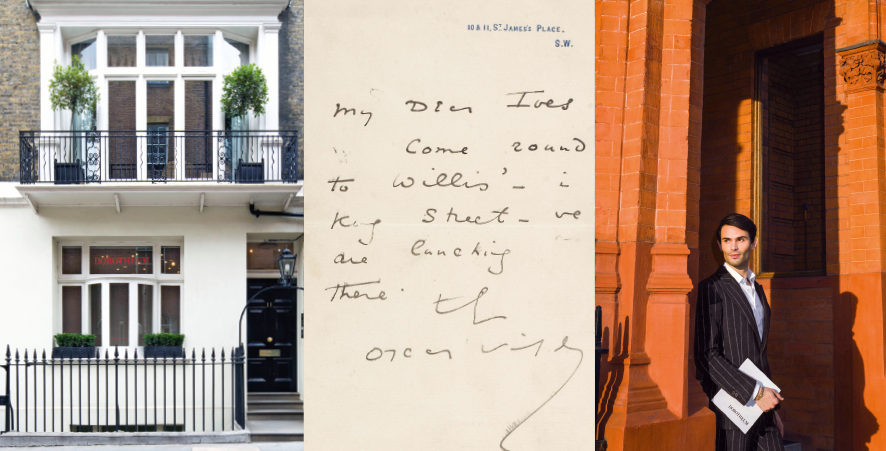

Why bright young things still yearn for old masters, the curse of minimalism, and how to bring Romanov glamour to the 21st Century: British society favourite, Mark-Francis Vandelli conducts a guided tour through his home, a pleasure palace once inhabited by Oscar Wilde in London’s Knightsbridge, discussing art, style and how he would present art bought at the Dorotheum. Sigmund Oakeshott of Dorotheum London was invited to Mark-Francis Vandelli‘s Cabinet of Wonders.

Between Virtue and Vice

Beneath the portico of a swaggering Victorian red-brick edifice stands Mark-Francis Vandelli, clasping a pamphlet of Dorotheum sales highlights, wondering if he should uncork some champagne to celebrate our arrival. “Like your Frans Francken picture, it’s the eternal Choice Between Virtue and Vice” he riffs. The society heartthrob is taking time away from his nigh-on half a million Instagram followers to discuss how a painting such as the Franken, famously sold by Dorotheum to a London dealer, could be incorporated into a fashionable interior of the “roaring (twenty) twenties”.

The heritage of Oscar Wilde

Behind the young collector, a bay window reveals his palatial new home for which he has martialed artisans to decorate, and has himself scoured sale-rooms to furnish, in order to create a transformation perfectly timed to coincide with the predictably sybaritic end of lockdown. And speaking of recherché hedonism, just as Dorotheum’s London premises are located in the same St James’s townhouse in which Oscar Wilde once kept rooms, Vandelli’s own Knightsbridge pleasure palace also once played host to the Anglo-Irish playwright: “While it was not his primary residence, this is where Oscar came to have fun!” he tells us. “But I was horrified to see what later owners had done to this building; it had linoleum floors, dropped ceilings and any of its original neo-Flemish character had been completely effaced. Almost like a second Iconoclasm. But then again, it was a blank canvas, so it was as exciting as it was sad. It was a challenge to transform it.”

Eclecticism of the 21st century

We pass under a newly installed, spoliated Baroque pediment into a pastel-coloured, stuccoed salon that is as close to a modern Wunderkammer as a 32-year-old might construct. It boasts a bronze BAFTA award, giant sphinxes and a tortoise shell, amongst other treasures, and “should ideally have been octagonal” confesses the erudite Vandelli. He excuses himself to dart behind a Lucio Fontana concetto spaziale which hangs upon a mirrored bathroom door, flanked by two rock crystal obelisks, before continuing: “Contemporary design can be so anodyne and predictable – the idea of beauty remains largely monochrome and dominated by straight lines. The great joy of living in the 21st century is that we no longer need to be tied to strict stylistic codes. We have the freedom to juxtapose elements from different periods and places in a way that truly reflects our own aesthetic. If the proportions are correct and there is sense of balance and coherence, there need be few rules. Look at cosmopolitan London, it is as architecturally eclectic as Vienna’s Ringstrasse – a true pastiche of European styles. I am part Italian, part Russian, and grew up between London and the South of France, and this home is somehow an expression of that.”

I point out that his reliefs of dancing nymphs and light blue plaster are redolent of the Hermitage and he concurs: “Precisely! I borrow elements and repropose them to my own liking – which is also what makes the Russian taste particularly sophisticated – they took the best of 18th century Italy and France and combined the two to create a new and most refined style.” And filled the palace with 17th century masterpieces from the Low Countries such as the Francken? I suggest. The “Infant Christ with Saint John the Baptist” by Peter Paul Rubens in Dorotheum’s last sale for example, suits Russian taste, declares Mark-Francis. “It was the most charming work and typifies everthing Rubens is best known for. The delicacy with which the hands and facial features are rendered, the treatment of the figures in relation to the background. It is as elegant and refined as one could wish for.”

Contextualising Art

We ask Mark-Francis to name his three favorite old master paintings. The influencer expounds: “Every great artist in the contemporary world, whether it be Jeff Koons, George Condo or whoever else, is inevitably under the influence of the history of art and the Old Masters because art is intrinsically evolutionary. No art can be created within a void. I have chosen the Francken because it reminds me of Dante’s Inferno and his own hellish depictions drawn from Ovid’s Metamorphosis. We are ever on a journey. I also love the four anthropomorphic representations of the seasons by Lo Spadino, which were sold at Dorotheum in 2017. They have such wonderfully playful appeal to anyone with good taste and humour! Hugely decorative, joyously inventive, and utterly timeless. Particularly the most Baccahanalian of the four pictures, which is rapt with pomegranate-bearing elegance. I generally like to buy things in pairs, but a series of four is most exciting as you can create a whole scheme around the works. Perfect for dining room, I think!

We ask Mark-Francis to name his three favorite old master paintings. The influencer expounds: “Every great artist in the contemporary world, whether it be Jeff Koons, George Condo or whoever else, is inevitably under the influence of the history of art and the Old Masters because art is intrinsically evolutionary. No art can be created within a void. I have chosen the Francken because it reminds me of Dante’s Inferno and his own hellish depictions drawn from Ovid’s Metamorphosis. We are ever on a journey. I also love the four anthropomorphic representations of the seasons by Lo Spadino, which were sold at Dorotheum in 2017. They have such wonderfully playful appeal to anyone with good taste and humour! Hugely decorative, joyously inventive, and utterly timeless. Particularly the most Baccahanalian of the four pictures, which is rapt with pomegranate-bearing elegance. I generally like to buy things in pairs, but a series of four is most exciting as you can create a whole scheme around the works. Perfect for dining room, I think!

Finally, he walks to the opposite wall and unhangs a seicento work from his own collection, casually bringing it over to lie among the golden damask silks of the chairs and pouffe on which we sit. “I have many things that were perhaps once intended for churches or private chapels, despite the fact that I could hardly be called a foot soldier of the Counter Refomation. This Saint John the Evangelist of the Emilian School was previously hung in my mahogany library as I thought Saint John’s scarlet drapery looked marvellous next to the red leather bindings. Collectors don’t always need to be consumed by the iconography of a work. The moment you extract a picture from its original context and put in another, it can take on new meaning – and that is, after all, one of the great joys of owning art rather than merely appreciating it in a museum.”

Read the new myART MAGAZINE