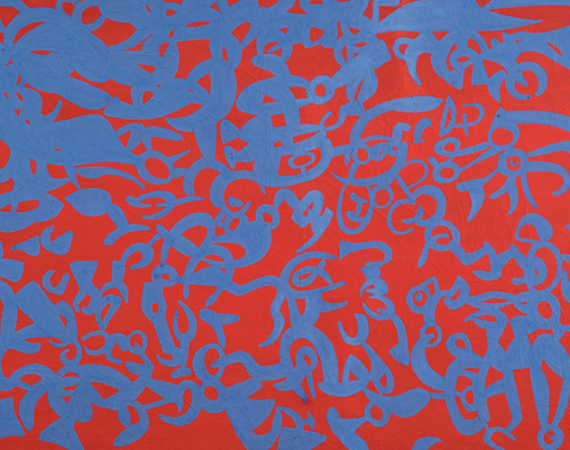

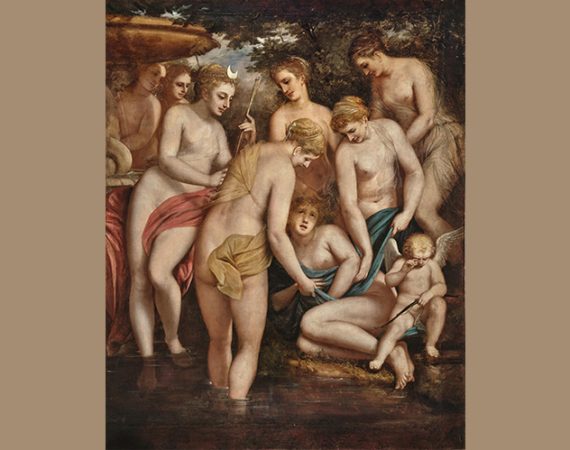

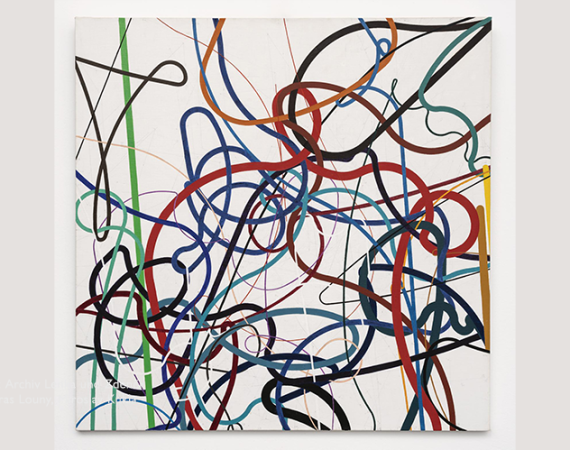

Trois têtes (1960) is a striking example. Three faces emerge from the page: on the left, a figure crowned with laurel seems to allude to Dionysus, a poet, or a sage. The nervous strokes carve into the paper with determination, while the dark areas envelop the figures in a shadow that is at once memory and the flow of time. The features twist and intensify, until they become masks: the grotesque traits of the central figure recall the visage of Socrates. The heads, almost deformed, establish a silent dialogue between youth and old age, myth and philosophy. While Trois têtes emphasises the psychological, Écuyère et tête (1969) opens itself to symbol and dream. On the left, an Amazonian figure on horseback emerges like an ancient vision: her body, more than a figure, is a fragment of myth dissolving into an intricate landscape. From this point, the scene transforms into a feverish jungle – an organic tangle where eyes, faces, and forms surface like hidden presences, born more from the unconscious than from compositional logic.

It is a universe in which order yields to vital chaos, and every mark opens a passage inviting the viewer to penetrate beyond the veil, into the space where image and dream intertwine. The wide-open eyes emerging among the forms heighten this dreamlike tension: suspended presences that evoke the Surrealist imagination – from Man Ray and Magritte to Masson and Buñuel’s cinematic visions – where the gaze becomes a threshold between the visible and the unconscious. This is no coincidence: although Picasso never fully embraced Surrealism, he maintained a constant dialogue with it, assimilating the play with the subconscious, the metamorphoses of the body, and the use of enigmatic symbols, which he integrated into his own visual language without ever losing his identity.