Jil Sander has always drawn inspiration from art and architecture: they have been sources of courage and positive energy throughout her life and have helped shape her iconic style. myDorotheum spoke to the renowned designer about quality, unconscious influences and reinterpreting timeless classics.

Dorotheum myART MAGAZINE: Visual art plays a significant role in your life. You live surrounded by artwork, you have drawn inspiration from artists for your fashion designs, and you have collaborated closely with them. So, Jil Sander, when did your interest in art begin, and what does it mean to you?

Jil Sander:At first, art was almost a lifeline. Contemporary artists were a huge source of inspiration as I developed my vision for fashion. It was modern architecture that sparked my interest in art; so many new and striking buildings emerged in post-war Hamburg.

© Peter Timm / Ullstein Bild / picturedesk.com

Can you tell us about the first artworks you bought, and what made you decide to purchase them?

In the 1960s, I became fascinated with Pop Art and Arte Povera. I bought several pieces, including an Andy Warhol silkscreen of Marilyn Monroe, as well as works by Jannis Kounellis and Mario Merz. These movements were diametrically opposed yet they were both equally emblematic of their time. I also acquired works by Cy Twombly early on.

Which artists have inspired your work? How does engaging with the work of artists such as Agnes Martin, Robert Ryman, Alighiero Boetti and Lucio Fontana influence your fashion designs?

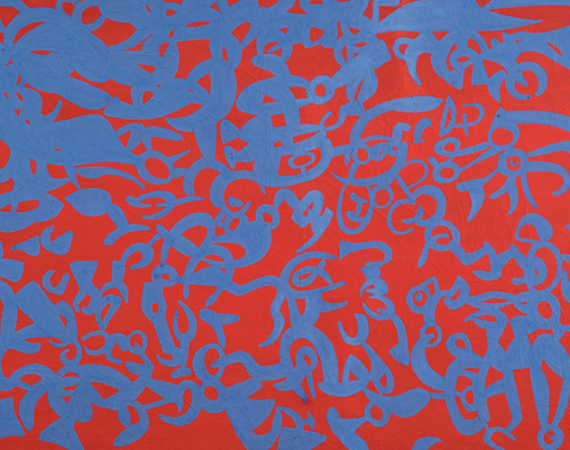

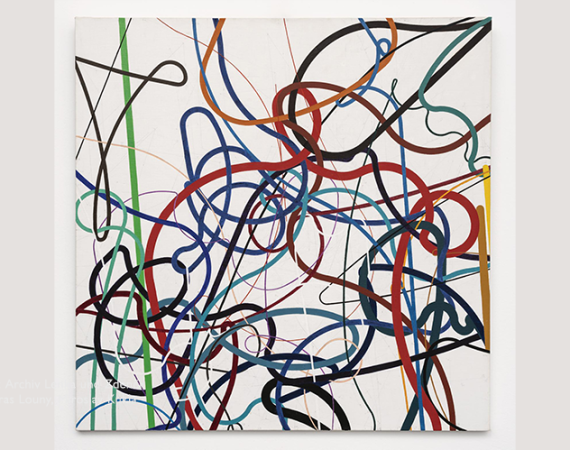

All of the artists you mentioned have been a great inspiration to me. I’m particularly impressed by the incredible complexity behind the apparent simplicity of Agnes Martin’s striped and network paintings. The simple lines and restrained colours are deeply moving and evoke intense feelings without the use of any conventional means of representation. Her work is a rich source of positive energy. She and Robert Ryman, with his minimalism, showed that less can indeed be more. I also admire fashion that captivates purely through its cuts, proportions, and volume, rather than relying on strong colour accents or gender-specific conventions. Lucio Fontana, in particular, showed that a statement can be made quite literally through bold cuts. Sculptors such as Richard Serra and Donald Judd reinforced my belief that volume speaks for itself. Alighiero e Boetti helped me see my mistrust of prints in a new light. While conventional patterns can become tedious through mechanical repetition, Alighiero e Boetti’s works, which at first glance may appear to be mere patterns, draw the viewer into their depths. I was also struck by his Arte Povera approach, in particular by his collaboration with Afghan weavers, whose precious craft is under threat of extinction.

In 1996, you collaborated with Mario Merz on a large-scale outdoor sculpture for the Florence Fashion Biennale. What was it like working with him, and what connects you to the Arte Povera artist?

This special edition of the Biennale was conceived by art historian Germano Celant and American journalist Ingrid Sischy, who wanted to bring together fashion designers and artists. I was given the opportunity to select an artist to collaborate with, and fortunately Mario Merz agreed. Together, we created a large metal cylinder on a hilltop above Florence, covering its ends with a special gauze that allowed viewers to see the city as if through a kaleidoscope. Inside, an invisible wind generator stirred flowers and leaves. I met Mario Merz several times in an Italian factory in preparation for the Biennale. He was an exceptionally likeable and calm person who concealed his ideas inside works that were both intriguing and easily approachable.

What are the defining characteristics of quality – in art and fashion?

Quality is something you recognise instinctively, without the need for words, and this applies to everything. It’s about technical excellence and complexity, as well as a sense of humanity that feels real, not theoretical. Quality creates a certain sense of excitement, making you feel as though you are part of something magical. Once you’ve experienced it, you will want to share it with others; quality is very communicative.

You commissioned Italian interior designer Renzo Mongiardino to design the interior of your Hamburg villa. What is it like, as a purist, to live surrounded by Renaissance wall panelling?

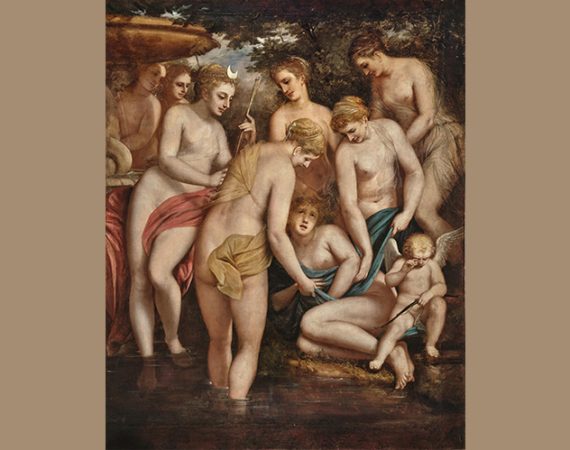

Renzo Mongiardino was more than just an interior designer; he created mise-en-scène and was a master of atmosphere. This is why he was in demand from film directors such as Luchino Visconti and Franco Zeffirelli. Rather than simply presenting me with a finished design, Renzo and I developed the interior together, step by step. The process enabled me to understand and connect with his ideas. Thanks to his expertise in history, I gained invaluable insight into the fact that purism is not a 20th-century privilege. He knew where to find authentic elements of an historical style and had the skill to commission missing pieces from highly experienced Italian craftsmen. He convinced me that quality is consistent across eras. A modern interior would never have suited the Martin Haller building, which, although historical, had been extensively altered during a restoration in the 1950s.

Which historical art period would you feel most at home in?

Thanks to my long-standing collaboration and friendship with Renzo Mongiardino, I can no longer answer this question definitively. Previously, I would have said the 1920s because the spirit of experimentation, knowledge and creative daring that characterised that period continues to inspire me.

Your major exhibition, Jil Sander: Present Tense, which took place at the Museum Angewandte Kunst in Frankfurt in 2017/18, highlighted the full scope of your work, including fashion, product design, architecture and garden art. Does your connection with nature also inform your fashion designs? It has been suggested that your +J collections for Uniqlo reflect the parallels between the cycles of nature and fashion …

I live with nature, even in the city. It is our greatest teacher with its endless variety unfolding differently year after year, and its subtle chance compositions constantly transforming. When it comes to the use and orchestration of colour, nature remains my greatest – usually unconscious – source of inspiration. It never imposes itself, but anyone who pays attention will find its charms inexhaustible. Nature cannot be surpassed; it keeps us balanced and rejuvenates us.

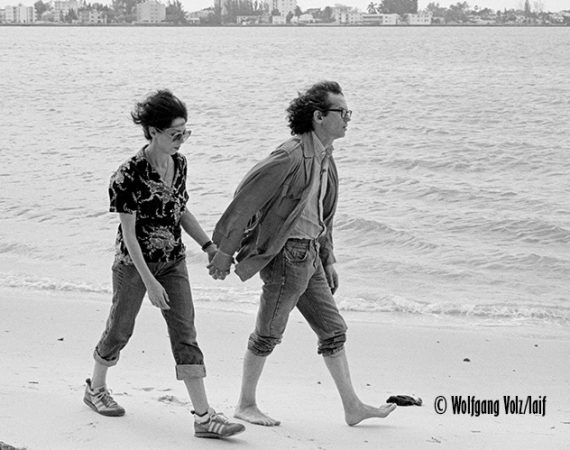

Decades ago, it was highly unusual for designers to promote their work using their own image. Yet, for the launch of your perfume Woman Pure in 1977, the distinctive, bold lettering was accompanied by a photograph of your face. You were involved in shaping the entire campaign, down to the smallest detail. How did this innovative idea come about?

The idea came from Jürgen Scholz of the Hamburg advertising agency Scholz & Friends. I spent a long time talking and discussing things with him to convey my vision. At one point, he interrupted me and said, “You keep saying ‘pure, pure, pure’, so let’s call it that. If you believe in it so strongly, you can put your face to it as well.”

From fabric development to shop design, what is your view on the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk? Of course, as Viennese, we immediately think of the Wiener Werkstätte …

I am very comfortable with the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, as long as it extends beyond the realm of art to encompass the shaping of everyday life, as the Wiener Werkstätte did. Each era develops its own aesthetic sensibility, seeking expression in every aspect of reality. Through successful design of our surroundings, we establish ourselves in the present and can act accordingly within it. It is natural for me to apply the design principles I use in my work to other areas, even if only in thought.

Another Viennese perspective: in Ornament and Crime, Adolf Loos criticised the waste of precious materials and the use of empty ornamentation and unnecessary decoration. Would you agree with him?

For the most part, yes, although I don’t agree with his moral stance. Over time, however, I’ve learned not to dismiss ornamentation outright. Working with it in a modern way remains a challenge.

You held a professorship at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna from 1983 to 1985, succeeding Karl Lagerfeld. What did you gain from your time there?

The fashion class was big, and we spent a lot of time debating and working on designs. We even staged our own show. Although I was barely older than the students, I valued the opportunity to learn from them and understand their perspective. At the time, Vienna still felt very Eastern to me. It is a remarkable city, whose history and lifestyle can be felt everywhere.

You took your first step into furniture design in 2025 with Thonet, reinterpreting Marcel Breuer’s iconic S 64 cantilever chair. What connection do you have to the Bauhaus vision? Would you say its influence is evident in your fashion designs?

Walter Gropius founded the Bauhaus as a place for the renaissance of craftsmanship. Later, however, it turned towards high-quality industrial production. However, its connection to the past, particularly with regard to innovation, never disappeared. I share the awareness of standing in a tradition of classics that must be translated into new materials, forms and proportions. Initially, I struggled with the idea of not being able to alter the design of Breuer’s cantilever chair. Ultimately, we agreed to breathe new life into the chair and make it more relevant in the contemporary world, as its bold design had become overlooked due to its familiarity. I approach fashion in the same way, reinterpreting classics, be it a trench coat, a T-shirt or an origami dress.

Are there any plans to develop the Thonet series further?

Yes, it’s already in the works. There will also be a table that can be used for private meetings and conferences, as well as a lounge chair with an ottoman.

Through your fashion, you have helped to shape a new image of women. Do you think art and fashion can change society, and what is your view on the current situation?

Art is a powerful driver of societal change. When people queue for modern art exhibitions, this inevitably influences tastes and attitudes, encouraging tolerance and openness to new ideas. Conversely, a lack of innovation in fashion can contribute to societal stagnation; the return to traditional female roles after the Second World War is a case in point. By innovation, I don’t mean shock or provocation, but rather the organic evolution of qualities and iconic designs. Although the era of global expansion and corporate consolidation in fashion has slowed, I remain optimistic that fashion will regenerate as a societal force through youth and small, independent brands.

JIL SANDER

is one of the world’s most influential fashion designers. Born in Hamburg, she has consistently championed an elegant, minimalist style, favouring volume, daring cuts, and innovative, high-quality materials over ostentation. Heidemarie Jiline “Jil” Sander studied textile technology at the School of Textile Engineering in Krefeld, Germany, until 1963. She continued her education as an exchange student in California in 1964. Following work as a fashion editor, she established the Jil Sander fashion company in Hamburg in 1968, selling her own designs alongside renowned brands such as Sonia Rykiel. In 1973, she founded her eponymous label. The launch of her perfume and cosmetics line in 1979, promoted through innovative marketing, significantly raised the profile of the brand. In 1989, Jil Sander was the first woman to list her company on the German stock exchange. The award-winning designer entered into a joint venture with Prada in 1999. From 2009 to 2012, she created the successful democratic line +J for the Japanese company Uniqlo. Following several changes of ownership and creative leadership, the Jil Sander label has belonged to the Italian OTB Fashion Group since 2021.

In 2024, the 360-page illustrated book ‘Jil Sander by Jil Sander’ was published by Prestel Publishing. Many thanks to Prestel Publishing for granting permission to reproduce the photos in this article.