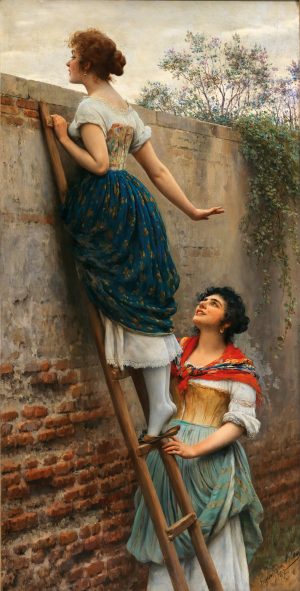

For this issue of Dorotheum myART MAGAZINE, a writer was once again inspired by a painting offered at the Dorotheum. This time: Ana Marwan with a painting by the artist Eugen von Blaas! We should set up walls. Because. As soon as a wall is set up, someone always turns up who wants to look over the edge. Because. It’s important to look over the edge.

There were no walls in Paradise; Paradise was wall-less. God created and created. God knows, it wasn’t enough … to create. Man soon lost interest in it, so God kept creating, became more and more creative, thirty thousand types of beetle and three million types of fungus, and then he thought about inaccessibility, which would arouse curiosity. Before he thought of the forbiddance, he thought of inaccessibility and created, in the depths of the ocean, in the blackest darkness, a fish, and gave it a headlamp, not so much for it to see, but for it to be seen, the funny fish.

But the two humans went on lying under the tree, not knowing that in the darkest depths under the surface there existed something to discover. The water surface wasn’t wall enough. Too yielding, too transparent.

The first successful prototype of a wall, therefore, was forbiddance. Curiosity was created, and it was good.

No wall, no curiosity, no curiosity … standstill. The fact that we need still-standing walls as the very things to prevent standstill shouldn’t surprise us; we should have learned by now that everything is contradictory, has to be, if it came into being in one and the same big bang.

So. If you’re left with total freedom, you become slothful, you foul. This was tested enough in Paradise, the beta environment. Only when freedom is restricted are things set in motion. Everyone strives after freedom, yet we end up like apples: in stagnation and foulness. This is something we want to suppress. The fact that we decompose. Since slothfulness and foulness aren’t desirable states, complete freedom should only exist as a wish, but not concretely. Only the wall may exist concretely. A concrete wall. A concrete fortification against sloth.

There’s something else: company. We are afraid to do things alone. Only when there are two of us and more does curiosity overcome fear. Adam would never have bitten into the forbidden apple if he had been alone, and nor would Eve. Eve needed the serpent to tran- sit from fear to curiosity, and Adam needed Eve.

God, too, created company first, then restriction. He knew the score. And so, in the end, we found his hidden fish, too. We only needed a little time.

So, it’s rare for us to be courageous when alone, but as a twosome we quickly become overconfident, we go over the top. What good is

it if we look over the top when we can’t tell someone what we saw on the other side? If we haven’t got someone to hold the ladder and giggle?

A delightful form of curiosity, the giggly kind. That is to say: this is a form of curiosity that is delightful. There are many nuances in curiosity, so many types, almost like fungi. The one before the last is the mother of invention. Demarcating: the first makes you giggle, the last drives you out of Paradise.

What they have in common, all these curiosities: what is found … what is seen … must be told. Shared. Deo gratias, because …

Isn’t it the most unbearable thing to watch someone who sees what we don’t see?

Is there anything we want to hear more than what doesn’t want to be said?

Is there any spur that makes the imagination gallop wilder? Thousands of ideas are spawned in our brains. Tens of thousands! And even if it’s hundreds of thousands, not a single one will correspond with reality. Another thing that drives us wild.

I had some little rabbits which I fenced in so the weasel wouldn’t get them. Inside the fence, it was all meadow and sky, outside the fence were weasels and buzzards. Nevertheless. Rabbits are drawn to the fence like magnets. It doesn’t matter where the fence is; they find it and want to get to the other side, whatever it takes. Because. Every Paradise wants to be lost.

I watched a little girl scratching a picture of a rabbit with her little claws. Before it was scratched away, the rabbit on the picture sat on its white bobtail and looked into the distance. I asked why she did it. “Don’t you like rabbits?” I asked. And she said: “yes”, but she wanted to see what it looked like from the front.

Ah, the other side of things. It’s always greener than the side they let us see. No other room in my childhood – and if I say my childhood, I mean ours – was as fascinating as the one with the door shut. “Don’t go in there!” The worst order in the young world.

In the pubescent world, I was/we were on a trip with our best friend. A shared room. One day, another friend of ours placed a letter on the bed, the envelope still closed. Our best friend read it, just like that. But was careful to put the letter back exactly where it was before. If this other friend had asked her to read the letter, she would have rolled her eyes, our best friend, and would have said whatever for. She couldn’t keep checking out her love letters, would be boring in the long run, we don’t have to share everything, do we, why doesn’t she shut up, this other friend, such an egomaniac, our other friend.

We all know this, don’t we? When someone stops in the middle of a sentence and doesn’t want to go on – “Oh, forget it …” – we are kicked out of our torpor, since talking is gone as a background noise, the silence nettles us: “You can’t do this, it isn’t right, once you’ve started you have to finish …” and even “That’s not fair.” And then, after everything has been said: “Well, that’s obvious, isn’t it?”

Ah, the unheard. The unseen. Columbus, too, wanted to get to the other side of the Earth, and Buzz Aldrin to the other side of the moon. This moon – we all know that it always shows us the same side of the coin, which is what it is. Buzz took Armstrong with him. When you’re a twosome, curiosity conquers fear.

But America has its seas and deserts, like the moon as well. The spur became dust and sand.

What do you see when you look over the wall? What does a young woman see who looks over it?

There isn’t a landscape that can live up to this question.

The only thing that would tempt us more would be the urge to hang this picture facing the wall.

But then we’d lose the human touch, the human hand, which is the very thing that turns curiosity into art.

The Author

Since completing her degree in comparative literature and Romance philology, the Slovenian-Austrian author, who was born in 1980, has been living in Vienna as a freelance writer. She writes short stories, novels and poems in German and Slovenian. This year, Marwan became co-publisher and managing editor of Literatur und Kritik, a German-language literature magazine. Der Kreis des Weberknechts, her debut novel, was published in 2019. In 2022, she drew attention by winning the Ingeborg Bachmann Prize for Wechselkröte/ Krota. Verpuppt, Marwan’s new novel, was published in February 2023 by Otto Müller Verlag. The Slovenian original, Zabubljena, won the 2022 Kritiško sito award for the best Slovene book of 2021.

AUCTION

19th Century Paintings, 2 May 2023, 6 pm

Palais Dorotheum, Dorotheergasse 17, 1010 Vienna

19.jahrhundert@dorotheum.at

Tel. +43-1-515 60-355, 765, 501