The Sacred in Everyday Objects

‘I’m a painter: I’m a visionary, but I don’t paint. I would like to attain vision, which is what painting was at first. Vision is the painter’s craft.’ (Jannis Kounellis)

To get Beyond the Boundaries

Jannis Kounellis, with roots in Greece and trained in Athens and Rome, sought to break free of the picture and get beyond the boundaries imposed by the canvas, so as ‘to embrace the world of the senses and join in with the vital chaos of reality’ (Germano Celant). As a painter he therefore resorts to radical means: Kounellis ‘paints’ with everything, horses and butterflies as well as iron and coal. ‘The use of materials is an act of liberation – a way to leave the picture behind. With this painful separation as a point of departure, we try to find a centrality that is never renewed but which nevertheless contains a novel idea,’ Kounellis says.

His quest is to exit the canvas.

In his quest of exiting the canvas, Kounellis took a direction that connects him to such artists as Jackson Pollock or Lucio Fontana, who similarly sought to free painting of given constraints and detach themselves from them: by removing the painting from the easel and placing it on the floor in the case of Pollock, making gesture the absolute protagonist, and by going beyond the two-dimensional surface in the case of Fontana through his gestural cuts. Having gained in depth and density, painting was no longer only two-dimensional.

Arte Povera

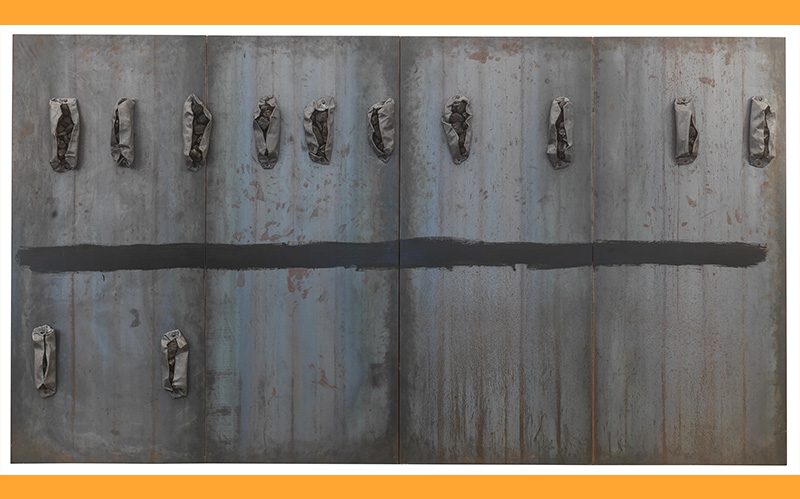

Kounellis even went one step further by abandoning the canvas and extending its space by increasingly treating it like a stage. In 1967 he exhibited together with Alighiero Boetti, Luciano Fabro, Pino Piscali, Giulio Paolini (find out more about Giulio Paolini here), and Emilio Prini at the Galleria La Bertesca in Genoa in a show entitled ‘Arte povera e IM spazio’. The title of Arte Povera gave the movement its name. For the presentation, the art critic and curator Germano Celant wrote a manifesto in which he postulated the characteristic features of the new current: the creation of revolutionary art, the elimination of iconographic conventions and the traditional language of symbols. Banal things became art, with the poverty of the material and the poverty of the means and effects being crucial. Under ‘poor materials’ the artists understood crude and ubiquitously available (found) materials, such as iron, coal, burlap, rags, stones, fire, and soil. Kounellis gave up the canvas in favour of iron plates on which he placed traces of life like old sacks or clothes. As painting imposed limits on the artist and oppressed his creative impulse it was necessary to go beyond the easel; if one wished to encounter reality one had to overcome and go beyond the closed space of the frame. In 1969 he exhibited twelve living horses at the Galleria L’Attico.

Jannis Kounellis

Today, Jannis Kounellis, who died in 2017, is considered one of the foremost artists of the twentieth century. Arte Povera stands for crucial developments in post-war art, having informed art of the 1960s and 1970s.

Kounellis’ works can be found in museums and prominent art institutions around the globe. Kounellis remained true to his visual language and, above all, his characteristic spectrum of colours – an unmistakable palette of grey, rust, and black smoke – for sixty years. In his works, he subtracts ordinary objects from the anonymous repetition of industrial mass production in order to make them unique and irreplaceable.

‘I’ve seen the sacred,’ he says, ‘in everyday objects.’