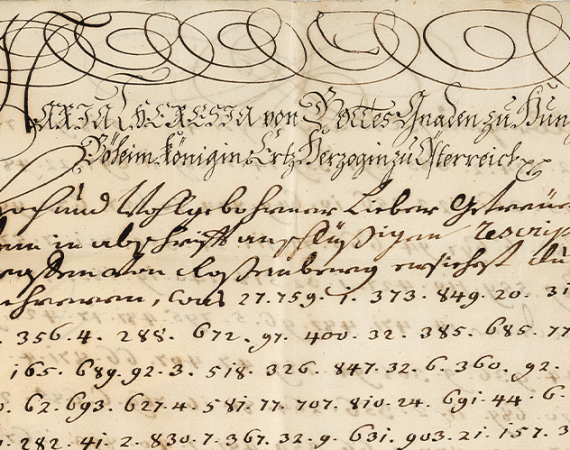

“Property of a Noble European House”: These words delight jewellery lovers and royal enthusiasts in equal measure, elevating unusual pieces of jewellery into something even more extraordinary. But where do these pieces actually come from? When were they worn? And by whom? Do they reveal more about particular historical events or about the personality of their wearers? A conversation with jewellery specialist, Astrid Fialka-Herics, and expert on the imperial household, Georg Ludwigstorff.

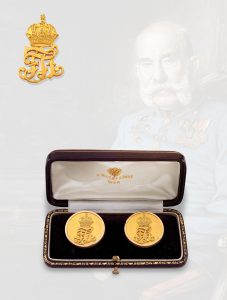

Kaiser Franz Joseph I. von Österreich

erzielter Preis € 6.400

What kind of noble or royal jewellery is sold at Dorotheum?

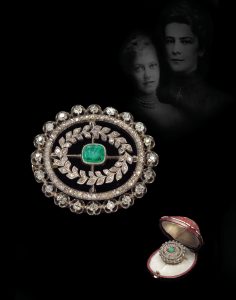

Georg Ludwigstorff: On the one hand, they tend to be small personal items formerly owned by the imperial family such as cufflinks belonging to Emperor Franz Joseph I, or a brooch given by Empress Elisabeth to her granddaughter, the Archduchess Elisabeth.

On the other hand, they are official gifts presented by the imperial family at receptions, on their travels and similar situations which would include items such as watches, bracelets, brooches, tie pins and so on. They usually bear the monogram of the respective ruler and are manufactured more or less elaborately, depending on the status and rank of the recipient.

Astrid Fialka-Herics: The range of jewellery offered at auctions often includes unusual tiaras, but also stomachers (also called “devant-de-corsages”: brooches worn centrally “in front of the corsage”), earrings, rings and other items from various European aristocratic and noble families. It’s always fascinating to discover who wore, or commissioned, which piece, for which occasion.

Is there a royal house which was particularly partial to jewellery, which was famous for its gifts, or which placed particular value on jewellery?

Georg Ludwigstorff: The House of Romanov was renowned for its gifts as we see in the records of Russian court jewellers. The Tsars gave away enormous quantities of gifts in the form of jewellery, but actually, almost all ruling houses including the Prussians, the Bavarians, the Danes, and the Dutch did as well.

ein Geschenk von Kaiserin Elisabeth von Österreich an ihre Enkelin Erzherzogin Elisabeth („Erszi“), erzielter Preis € 15.300

Astrid Fialka-Herics: When we talk about the affinity for jewellery, we must bear in mind that in some periods only nobles were allowed to wear real jewels, for instance in 18th-century France, and also in Austria after Metternich. That was what led Georges Frédéric Strass to develop a means of producing imitation gemstones in the mid-18th century, which is how “rhinestone” jewellery came into being.

Georg Ludwigstorff: There were also defined dress codes that stipulated who could wear what, much earlier on in history, in the Middle Ages.

Astrid Fialka-Herics: At that time, the most prominent clients of goldsmiths were still the clergy, and men were generally more elaborately bejewelled than women. This changed during the Renaissance period, when aristocrats and the bourgeoisie as well as bankers and, increasingly, women began to wear jewellery. Then, in the 19th century, with industrialisation and the growing wealth of the bourgeoisie, a new class became interested in high-quality jewellery.

Georg Ludwigstorff: Unsurprisingly, industrialist families also wanted a chance to display their wealth and there was much opportunity to vaunt their jewellery at the many parties and balls held at that time.

Astrid Fialka-Herics: And, as you mentioned, the Habsburgs were, in fact, more modest than others during the latter part of the nineteenth century.

Georg Ludwigstorff: Yes, particularly the last ruling generation – Empress Elisabeth was not particularly interested in jewellery, and Emperor Franz Joseph certainly wasn’t. In earlier generations however the situation was different – Maria Theresa and Franz Stefan

von Lothringen, for instance, lavishly built up the imperial jewellery holdings during the Baroque period.

Historically, was jewellery worn, or merely used for display?

Georg Ludwigstorff: Many pieces were only worn on specific occasions such as coronation ceremonies, weddings and the like. However, they were also exhibited, on public display, in the treasury, relatively early on. Jewels have always played an important part in elevating the image of the ruling classes.

Was there an actual office at court responsible for the provision of presents?

Georg Ludwigstorff: Yes, a strict distinction was made between objects purchased as gifts of state and at state expense, which was looked after by the Oberstkämmerer or Keeper of the Privy Purse, and those paid for by the emperor from his private coffers, known as the “Allerhöchsten Privat- und Familien Fond”.

Astrid Fialka-Herics: The gifts for Katharina Schratt, for example,

the fuchsia brooch …

Georg Ludwigstorff: … exactly, that was paid for out of the private coffers. The purchase of state gifts, however, would have been carried out by the Oberstkämmerer. There are records listing what, how much, and at what price, was purchased for which occasions …

What is so special about the fuchsia brooch you mentioned?

Astrid Fialka-Herics: That was one of our most spectacular lots here at Dorotheum. It was a gift from Emperor Franz Joseph to his mistress, the actress Katharina Schratt, which was manufactured by A. E. Köchert, Purveyor to the Imperial and Royal Court.

Georg Ludwigstorff: The Köchert company made a lot for the imperial family, but there were numerous other court jewellers: Rothe, Halder, Rozet & Fischmeister … You can often see who made the piece of jewellery by looking at the boxes, which are themselves also of great value to collectors today.

Anfertigung von A. E. Köchert im Auftrag der Erzherzogin Marie Valerie von Österreich anlässlich der Hochzeit ihrer Tochter Hedwig, erzielter Preis € 186.000

Foto © ÖNB/Wien Pf 43.106:E(1)

Have other important pieces of Habsburg jewellery been sold at Dorotheum?

Astrid Fialka-Herics: Yes. For example, the wedding diadem given by Archduchess Marie Valerie to her daughter, Archduchess Hedwig, on the occasion of her wedding to Count Bernhard zu Stolberg-Stolberg in 1918. Or a particularly beautiful oriental pearl and diamond tiara with a matching stomacher, which was also commissioned by Archduchess Marie Valerie.

What is the attraction of such pieces of jewellery of aristocratic provenance today? Who do they appeal to?

Astrid Fialka-Herics: Collectors and people who appreciate the splendour of bygone eras are interested in them. The special aura of historical pieces of jewellery is certainly an attraction at auctions. We see that in other departments too.

manufactured around 1900

estimate € 40,000 – 70,000

Is the jewellery actually worn today?

Astrid Fialka-Herics: Yes, definitely. Tiaras, for example, are often bought by families whose daughters are about to get married. A new piece also often complements an existing collection.

There was a real tiara craze back in the 1930s …

Astrid Fialka-Herics: The craze goes on. Tiaras are still in high demand, partly because they often offer different ways of wearing them – such as the beautiful turn-of-the-century tiara coming up for sale in June at Dorotheum: it is a particularly delicate piece that can be worn both as a tiara, and also as a necklace, or brooch.

Astrid Fialka-Herics is Head of Dorotheum’s Watches and Jewellery department, a gem expert, lawyer and trained goldsmith. Georg Ludwigstorff is a historian, art historian, and Specialist for the imperial household, medals and decorations, and silver at Dorotheum. Interview by Theresa Pichler, she works as cultural scientist at Dorotheum.

AUCTION

Jewellery, 2 June, 1 p.m.

Saal-Auktion mit Live Bidding

Tel. +43-1-515 60-303

jewellery@dorotheum.com