REFLECTION OF ETERNITY

He deconstructs and alters space: Anish Kapoor, one of the most celebrated sculptors of our time is transforming the great stately home, Houghton Hall in Norfolk. Through the installation of his sculptures and his use of mirrors, he addresses the dialogue between culture and nature, between what is natural and what is contrived, between chance and order. This exhibition, sponsored by Dorotheum, will show-case a collection of his work over the last 40 years an will be open till 1 November 2020.

Houghton Hall

This exhibition at Houghton Hall in Norfolk presents a new series of work by one of the most celebrated and influential artists of our time, Anish Kapoor. Kapoor’s stone sculptures and iconic mirror works will be displayed in Houghton’s monumental Stone Hall and in its spectacular grounds, designed by Charles Bridgeman in the 1720s for Britain’s fir t Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole. The contrast and the dialogue between nature and culture, between natural and artificial, between chance and order, are the leitmotiv of the Baroque, the period in which Houghton was conceived, and a key consideration in Kapoor’s work.

© Anish Kapoor. All rights reserved DACS, 2020 Photo: Pete Huggins

Reflections of reality and artifice

The use of mirrors is one of the main features of Baroque architecture, as can be seen in The Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles where seventeen gigantic mirrors reflect, in an almost linear continuity, the seventeen arcaded windows that overlook the gardens. They create the fundamental Baroque visual and conceptual dialectic between inside and outside, between reality and artifice, through which the relationship between the spectator and the surrounding space is altered and modified. The mirrors multiply the space, not only creating a disorienting effect, but also increasing the ways in which one sees and in turn, is seen.

Deconstruction and Transformation of Space

Courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery.

© Anish Kapoor. All rights reserved DACS, 2020

Photo: Pete Huggins

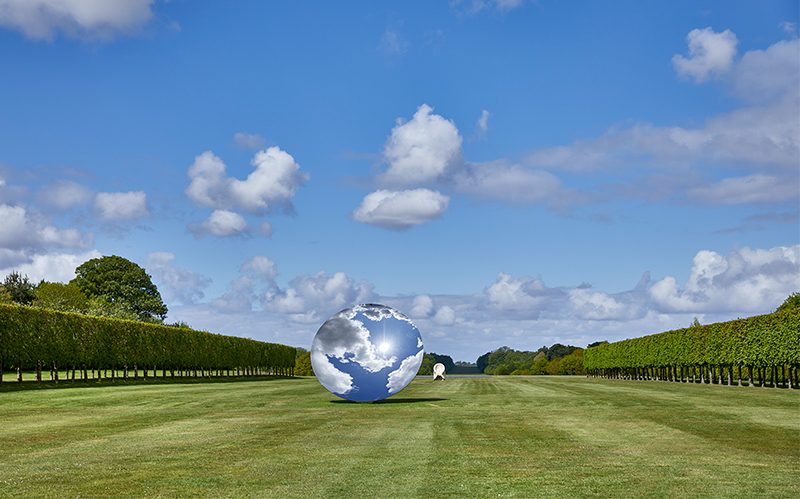

Substituting William Kent’s arrangement of the ancient Roman busts that surround Houghton’s Stone Hall with painted concave mirrors of fluctuating hues, Kapoor initiates a deconstruction and transformation of the space, which is both intimate and unsettling. While being portraits of infinity, these mirrors also reflect the self and make it aware of its own presence. They trigger its narcissistic dimension; but mirrors which constantly follow you through the whole space potentially prolong their effect, thereby changing one’s perception of time; they capture an eternal instant as in a photograph. Paraphrasing Proust’s “In Search of Lost Time”, they are almost able: to secure, to isolate and to render static for the duration of a lightning flash that which it can never wholly grasp, a fraction of Time in its pure essence. Mirrors have the power to duplicate the body that sees, transforming it into a body that itself is seen. As Merleau-Ponty has written, “… the phantom of the mirror displaces my flesh to outside of me, and at the same time, everything invisible about my body can affect all the other bodies I see. From this point forward, my body can be comprehensive of segments it lifts from the bodies of others, just as my own substance passes into theirs: human beings are each other’s mirrors. And as far as the mirror is concerned, it is the tool of a universal magic that transforms things into spectacle and spectacle into things, myself into the other, the others into myself.” The works by Kapoor which call such specular reverberations into play, through the use of concave and convex surfaces and structures, reflect and simultaneously transform us, along with our perception of the world and the perception of ourselves in the world. They undermine the very fundament of the proportions with which we measure our physical self and the things that stand around us. They form an oneiric self-portrait that revokes all definitive vision or experience of the self. The works clone the image by way of a deformation, a torsion that dilates or sucks the individual back towards the infinite. They deploy the ritual of art to reproduce and temporarily anaesthetize human desire. “Sky Mirror” (2018), installed on the long West Lawn, in front of the Hall, is a vast concave mirror of polished stainless steel angled up towards the sky. Its surface reflects the ever-changing environment, the movement of the clouds, the brightness of the stars, the flocks of birds, the nothingness and the infinite all of this and none of this. An oracle of light and ether, it dissolves its reflection into a perpetually modified and modifying message. Its materiality is dispersed into the boundlessness of the heavens.

Stone and Marble Sculptures

Courtesy the artist.

© Anish Kapoor. All rights reserved DACS, 2020

Photo: Pete Huggins

The indeterminate nature of boundaries and limits, the ambiguity of spatial coordinates, is also one of the determining factors in Kapoor’s stone and marble sculptures. Human in scale, organic and sensually enigmatic, immersed and engaged in the landscape and within the architecture of Houghton Hall and its park, they stand out like timeless totems caught between weight and void, gravity and flux, presence and tension. The tension of matter and materiality seems to be set free from its constraints, as in the eternal struggle of human beings to free themselves from their material trappings. The sculptures seem to duel between the tentative geometry and pressure of the form, their tactile and asymmetrical refolding into chance and the unforeseeable. The frequent presence of cavities within Kapoor’s sculptures elevates emptiness and shadow to the same level and visual conditions as fullness. All hierarchies of greater and lesser physical tangibility are expunged or inverted and rendered fluid. A state of suspension arises where objects cease to be only objects; absence and emptiness take on corporeal qualities, while matter takes on spirituality. The depths of the hollows which the work presents cannot be deciphered in volumetric terms, but are nonetheless grasped by way of their reflection in the spectator’s state of mind: they are forever wrapped in a veil of immensity, in a dawning metamorphosis that traverses and flows beyond the contemplation of a transitory moment. These void spaces set up a dynamic system in which matter and the gaze are both engulfed in a vertigo of interiority. Its vanishing point hovers in flight and disintegrates into radiating surges back and forth of being on its course to the infinite. This is even more evident in the two works exhibited in the new gallery at Houghton, entitled “Wounds and Absent objects” (1996) and “Not Eve” (1989). In these works, one comes to experience a kind of abyss in which the gaze can only get lost, while at the same time feeling itself surrounded, and attracted toward a chain of references and drives that bring about a fusion of individual memory and collective consciousness. The hollows blend into the flow of eternity, into the manifestation of darkness, of Eros, of birth and death and the impenetrable mystery they constitute. The senses crumble, sucked in toward a center. They enter the unknown, the unknowable, they sound the depths of invisibility. In all cosmogonies, the abyss sets up the terms of all subsequent evolution. It engulfs the present and recreates eternity. In ancient Greek and Latin, the word “abyss” denoted a state in which depths and heights are indefinable, the formless state of being that generates and stimulates transformation and evolution, in defiance of every form of solidity or fixity. Height, width and depth abstract themselves into a counterpoint of volumetric presence and inaccessibility, of hypnosis and failing vision. They dissolve by way of elision and antinomy into an atman, a vital breath, of light and darkness, into the intimate essence of every human being and everything, into universal consciousness.

Mario Codognato was the Chief Curator of MADRE, the new museum for contemporary art in Naples and Chief Curator at the 21er Haus in Vienna. He is now Director of the Anish Kapoor Foundation.

Anish Kapoor

is internationally regarded as one of the most prominent sculptors of his generation. He is best-known for spectacular, large-scale public installations such as “Orbit”, a landmark of the 2012 Summer Olympics in London, or “Dirty Corner” in Versailles made in 2015. Most of the London-based British-Indian artist’s abstract, poetical sculptures are conceived as a series; all of them reference their specific setting and involve the viewer. The same goes for his large-scales and stone sculptures and his convex and concave mirrors, which warp, swallow or reflect surfaces and environments. “My art is upside down and inside out”, Kapoor says. His series include works of wax mixed with red pigment, which can be interpreted as a contemporary reference to ancient cultures. In 2009, Kapoor’s installation at the Austrian Museum of Applied Arts (MAK), entitled “Shooting into the corner”, featuring a catapult repeatedly shooting wax projectiles against the museum wall, caused a sensation. By the end of the exhibition the sculpture had amassed a total weight of about 20 tons. Anish Kapoor represented Great Britain at the 44th Venice Biennale in 1990, received the Turner Prize in 1991, and contributed to documenta IX in 1992. He was awardeda knighthood in 2013.