On the occasion of the exhibition ‘Magic and Abysses of Reality’ at the Leopold Museum in Vienna, we talk to our Dorotheum specialist on 19th and 20th Century Paintings and curator of the exhibition, Marianne Hussl-Hörmann. In conversation, she sheds light on Rudolf Wacker, one of the most important representatives of New Objectivity in Austria. The Leopold Museum is showing Wacker’s oeuvre, which deals with the social and political tensions of his time and is to be understood in interaction with his person and his writings. He developed a precise visual language in his paintings. Hussl-Hörmann gives us in-depth insights into the concept of the exhibition and explains how to approach Wacker’s work and why it fascinates her personally.

The idea of organising an exhibition on Rudolf Wacker had been around for some time. Now there is the first monographic exhibition on Rudolf Wacker in Vienna for 66 years. How long was the exhibition in preparation, and were there any particular challenges or surprises during the conception?

Well, putting on an exhibition about Rudolf Wacker in Vienna is something that has probably already been discussed many times and has long been a desideratum, which the Leopold Museum has now actually realised. This also has to do with the fact that last year, in 2024, there was a major exhibition on German positions of New Objectivity at the museum. It was therefore almost logical to show an Austrian position now. And Rudolf Wacker is of course the first to be mentioned. That’s how it actually came about.

It was a very short preparation – in the end we only had nine months. And when the time window is so tight, the big challenge is of course to get the art works. We had the advantage that there are large collections relating to Rudolf Wacker – not least the Rudolf Leopold Collection. Then there is the collection of Klaus and Friederike Ortner, which is very extensive, and of course the Vorarlberg State Museum, which also has a very large collection. But otherwise his works are relatively poorly represented, and perhaps that is one reason why other museums have not yet taken up the cause.

Nevertheless, you need a lot of works from private collections, and finding these was the big question at the beginning. It wasn’t clear whether we would succeed – but we did. Most of the private collectors were also very keen to be able to show their work in public. Yes, those were actually the main challenges, and we mastered them quite well.

What was the reason that a Wacker exhibition has only now been organised again in Vienna?

I think it has to do with the fact that New Objectivity as a stylistic period is not so present in Vienna and has therefore not received as much attention. That has only changed in the last ten years. There are not many Viennese painters who can associated with New Objectivity – rather periods of work within an oeuvre. But the most consistent and coherent approach you can find is in Franz Sedlacek, who was also discovered late, but ultimately can’t compete with Wacker.

Perhaps an East-West divide also plays a role here – that this period was not so much in focus in Vienna and was therefore not recognised for a long time.

Around 200 exhibits have come together. How was the selection made, particularly with regard to the reference works by artists such as Otto Dix or Anton Räderscheidt?

We actually referred to the previous exhibition because there were already some good works there that we simply adopted. It was also important for us to focus clearly on Wacker. When you introduce an artist to a new audience after such a long time, too much comparative material can be more confusing than useful.

We only showed very selective contrasts – for example: What has Wacker not painted that others have? Or which motifs – such as the cactus – have been adopted by other artists?

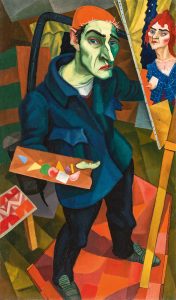

What we are particularly pleased about and I think is also important is that we were able to show Otto Dix’s self-portrait and juxtapose it with a self-portrait by Wacker. You can see directly that Wacker is referring to the painting that he saw in an exhibition a year earlier.

I found it very interesting to read the quotes from Wacker in which he says that pictures should act like books and drawings like letters. To what extent does Wacker’s written oeuvre (diaries, letters) play a role in the exhibition, and what do they tell us about the artist?

Yes, that’s a very good hint. It was very important for us to show that Wacker is not only perceived as an artist, but also as a great reader – ultimately as an intellectual, as a very educated person. He had a very large library by the standards of the time and read an incredible amount and variety of literature over the course of his life.

But he also wrote a lot himself – diaries, many letters. This results in an overall concept: painter, writer, reader – in his work, they merge into one another. His pictures look like painted diary entries, and his language is so lively and eloquent that you can also see pictures in them. There is a very beautiful interaction between word and image.

You often recognise a mysterious mood in Wacker. Is this in harmony with his reading or his interests?

No, in his notes he is very sober, almost analytical. He writes many reviews of exhibitions that he has seen and is very clear and unsentimental in his approach. He is not mysterious – more reflective, philosophical in his thinking.

I think he realised that pictures have a different language to words. And this inevitably makes them mysterious.

Wacker dealt intensively with his own identity, particularly in his self-portraits, but also with his environment. To what extent did the political and social developments of the 1920s and 1930s influence his work?

Very strongly. He is a child of his time – a time in which one would not have wished to be present. He was very aware of political and social developments and commented on them as much as he could.

After his time as a war prisoner, he first became very preoccupied with himself. After all, those were the wild 1920s – a time full of hope, but also a bit of madness. You can sense this in his paintings: they are loud, the colours are very vibrant and there are many different objects in the room. You can really feel how his head is buzzing and how he throws himself into life full of vigour.

Then came the economic collapse of 1929, and the political situation became increasingly tense. During this phase, he reacted by withdrawing the objects: he thematised emptiness, the tension between the objects. He found various means of expressing this growing anxiety. There is thus a strong interaction between art and current events.

Could you say that he is commenting on his time – but subtly?

Exactly. He himself says that you have to become more and more secretive. He was afraid – and certainly had no desire to go to prison again. So he created a code of images that you can’t actually decipher. It is very self-interpretative and gives no clues.

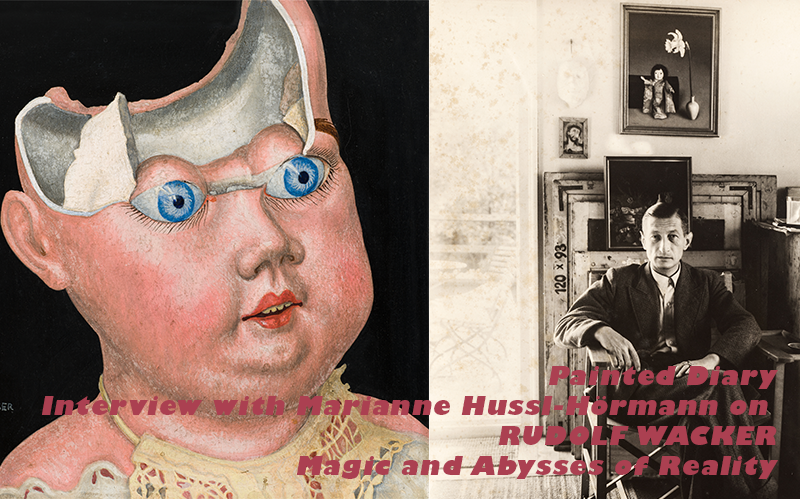

That would have been my next question. His still lifes are often composed with found objects, dolls or withering plants. Is there any indication that he deliberately used these objects as symbolic ciphers, or is it a very personal language where you can only guess what was meant?

It is exactly the same. The objects he draws change. As I said, the 1920s are very much about him as a personality and also about his relationship to women, to his own wife, to others, to his erotic needs and experiences. There are souvenirs from his travels and also from his imprisonment. Each picture is a portrait of himself.

And in the later phase, he is no longer so interested in himself, nor is he interested in interpersonal and private interpersonal relationships. You almost get the feeling that he creates a spell around himself with fetishes and things that also ward off evil or strongly thematise it.

Once you have understood this a little in this respect, you might come up with interpretations that are coherent – but perhaps he was thinking of something completely different. You get a rough idea of how he makes a statement with these objects.

Wacker moved from Expressionism to New Objectivity. Are there any works in the exhibition that make this stylistic transition particularly visible?

We have a room where we also show the objects from his estate in display cases, which are then reflected in the surrounding still life paintings. And there you can already see that part of the 1920s is still characterised by horror vacui, he is still quite loud. And on the other hand, there is the smoothness and this flawlessness.

But it has to be said: He’s never either up or down, he’s always a lot in between. And he continued to use this gestural, if you like, expressive style of painting later on, especially when he painted landscapes or city profiles on location, working very gesturally and impulsively, in the moment.

And he then takes these motifs with him and reworks them later in the studio into such fine, newly objective pictorial worlds. You can really see the artist’s way of thinking here: from the immediate to the reflective and intellectualising.

And the exhibition is entitled ‘Magic and the Abysses of Reality’. Wacker is also described as a magician of the everyday. Apart from the magical, what other keywords could be used to describe Wacker in a few words? You also mentioned intellectualisation and reflection. Are there any other keywords that apply to Wacker and his development?

I would simply describe him as a great storyteller. That probably says most of it, because every story is also a kind of magic or an underworld, so to speak.

He was an entertainer, very sociable and quite humorous. People really enjoyed talking to him – he had a lot to say and knew a lot too. This narrative style is also present in his pictures. That’s why it’s always so nice to engage with them.

It’s not just depressing – actually, it’s not depressing at all. It takes you into the depths of life. And I find that very beautiful.

What interests me personally: Has the history of reception changed over time? In other words, how is Wacker perceived today compared to his own time?

I think so. He always lived in Bregenz. For the normal public, he was certainly a weirdo, enigmatic and peculiar.

And it’s also the case – this applies to all times – that the viewer is naturally slower to develop than the artist. This colourful potpourri and then again these so obviously enigmatic constructions could of course not be understood immediately.

But he also had collectors – good entrepreneurs, wealthy people – who understood this in conversations and realised that he was a genius. They also supported him or bought his works at expensive prices.

Today it also took longer. New Objectivity is a period that was hardly recognised in museums for a long time – this applies not only to Austria, but also to Germany. It was also due to the interwar period: for a long time, people didn’t want to know anything about it.

Only now is it coming back. In research, more and more different perspectives are being used to shed light on the fact that these works of art are also technically fascinating.

Of course, something has already changed. You can also see that in the reviews of the Wacker exhibition – there is now a completely different openness and also a certain knowledge base.

Then perhaps as a final question: is there a favourite work?

Several, stupidly enough. A favourite work for me is actually one that deals with nothingness and silence. It’s in the penultimate room, where all you can see is an empty vase, a mask, a shell and a bulb of garlic on a whitish-grey background. It’s incredibly fascinating.

And these late withered flower still lifes also have a special fascination and beauty that is almost unrivalled.

Leopold Museum – Rudolf Wacker

Magic and the abysses of reality

30 October 2024 to 16 February 2025

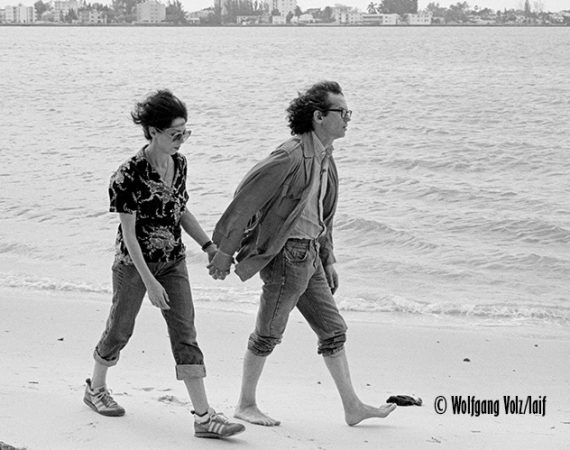

The Leopold Museum Vienna is dedicating a comprehensive exhibition to the Austrian painter Rudolf Wacker (1893-1939) entitled ‘Magic and the Abysses of Reality’. Wacker, one of the main representatives of New Objectivity, achieved international recognition for his precise visual language and mysterious depictions of everyday objects and landscapes. With numerous works from public and private collections, Wacker’s artistic development from late Expressionism to New Objectivity and his confrontation with the social and political reality of the interwar period will be shown. Reference works by Wacker’s contemporaries such as Otto Dix, Alexander Kanoldt and Anton Räderscheidt complement the exhibition. The curator alongside Laura Feurle is art historian Marianne Hussl-Hörmann, an expert in 19th and 20th century painting at Dorotheum. She has already curated three exhibitions at the Leopold Museum from 2016 to 2018 on Theodor von Hörmann, Anton Romako and Olga Wisinger-Florian.