How do we perceive jewels on people? What effect does jewellery have on us?

Helmut Leder, psychologist and an expert on perceptual aesthetics, in a conversation about beauty and jewels.

Aesthetics, psychology of the arts, design- and face perception – these are key research areas for Helmut Leder, Professor of Cognitive Psychology and Head of the Department of Basic Psychological Research and Research Methods at the University of Vienna.

Leder: Interestingly enough, there seems to be little or no research on the role and effects of jewellery. So in terms of research on the empirical effects of jewels, we can only draw conclusions from similar studies. We know a lot about what types of faces and facial features are perceived as beautiful. For example, our task group took a closer look at the effect of glasses on facial perception and found that they still make people look more intelligent and reliable, albeit less attractive. We also found that glasses draw attention to an important part of the face – the eye area.

Dorotheum myART MAGAZINE: People have always worn jewels as a status symbol. Jewels represent power. They say something about the class we belong to and express interpersonal affection. What factors shape the way we see a person who is wearing jewellery?

The answer is in the question: it’s the relationship between the beholder and the beheld. Peers tend to admire, appreciate, or even envy jewellery on one another, while a bejewelled person in a position of social superiority might trigger respect – and sometimes intimidation – in a beholder of lower status. Just think of royal crowns, insignia, judges’ and deans’ chains of office and the like!

Does jewellery make us more beautiful?

It depends. Jewels – especially beautiful ones – enhance a person’s face and characteristics. Jewellery can distract from less attractive features or conceal them, but it can also highlight beautiful parts like beautiful eyes, for example. Our studies indicate that, sometimes, what we perceive isn’t beauty as such but imperfections. We turned images of faces upside down so they would be more difficult to read. And guess what: they were found to be not less, but more beautiful!

Does jewellery change the beholder’s perception of the symmetry, say, of the face?

Yes, that’s a possible effect. By adorning a face left and right with something identical, something beautiful like earrings, you increase the “visual weight” on both sides of the face. Facial symmetry is indeed perceived as beautiful. There’s probably a biological explanation for this, because we associate symmetry with health.

But jewellery is also subject to fashion of course: in the 1980s, everyone was mad about sumptuous gold chains and bulky earrings, and what we’re seeing now is a tendency to minimalism and purism. Do we find “less” to be “more aesthetic” nowadays?

I’m not a sociologist, but my guess is that such fads have to do with more than just making new things fashionable or reviving former trends; they also reflect social and economic conditions.

Jewels have all kinds of shapes: they can be smooth, round and curved, or angular, edged and rectilinear. Are there any scientific studies on whether or not we perceive particular forms as more beautiful, and if so, which?

Many findings suggest that people feel more comfortable with round shapes. One explanation is that edges bear a certain risk of injury. A group of fellow researchers from Boston have demonstrated that brain areas associated with fear are less active at the sight of round objects. This is born out by our findings on how people perceive round interiors as opposed to cornered spaces.

Does the material from which jewellery is made also have a significant effect on our perception of it?

It certainly does, because we tend to associate different materials with particular values. But this is also subject to fashion, or psychological effects. Some people find it more important to flaunt their social status and economic success than others. Cognition and recognition are also decisive factors in aesthetics. In terms of jewellery, I suppose that this applies to the goldsmith and workshop, but also to particular stones and metals.

_

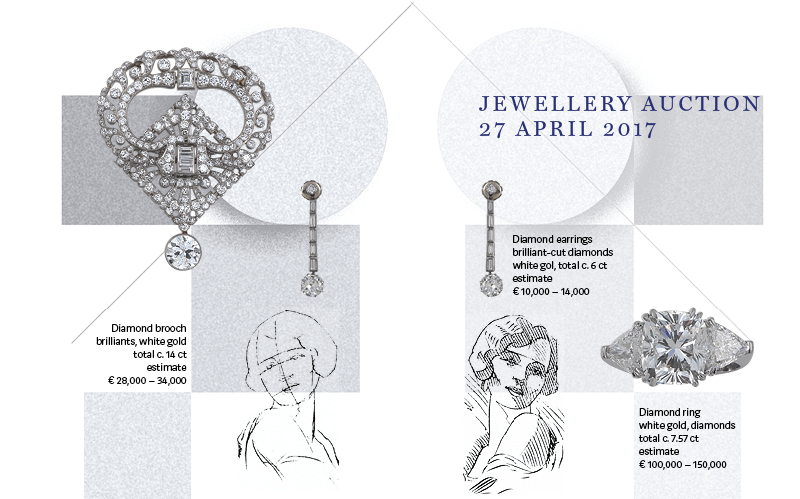

Jewellery Auction

27 April 2017, 2 p.m.

Palais Dorotheum

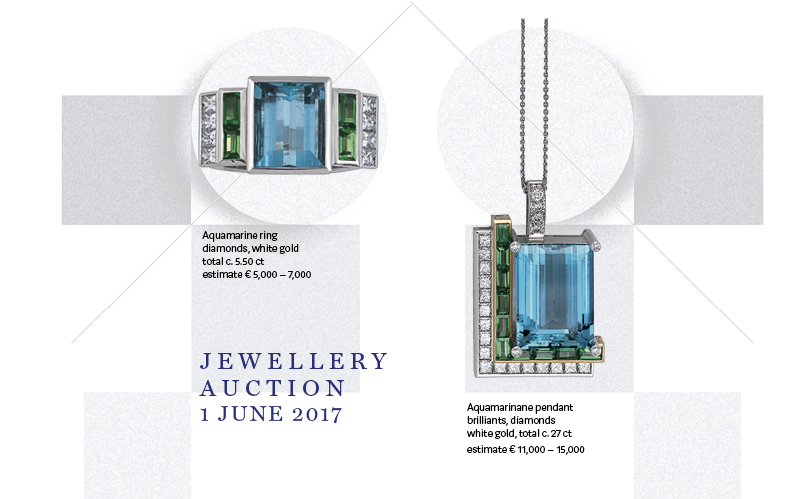

Jewellery Auction

1 June 2017

Palais Dorotheum