The jewellery collection of the Esterházy family

Extraordinarily extensive and well-documented, the jewellery collection of the Esterházy family contains sketches, inventory lists, and portraits of the women who wore the ornaments. It provides an interesting insight into Baroque jewellery art and its place in families and society. A story told by historic jewellery.

A Remarkable Collection

Among the lovely foothills of the Rosalia Mountains, Forchtenstein Castle looms proudly and majestically over the parish numbering around 2,800 inhabitants. Once a stronghold against the Turks, it now houses an important private collection of Baroque jewellery art.

Palatine Nicholas Count Esterházy, who began this collection, was a sure hand at marriage matters: both his wives – after the death of his first wife, Ursula Dersffy, he married Christina Nyáry – brought their widow’s inheritance to the marriage. This laid the foundation in the first half of the 17th century for the collection of decorative treasures that remains at Forchenstein Castle to this day. From the very beginning, the aim was not just to expand the collection, but above all to keep it together.

It is important not for its purely material value, but for its artistic quality and craftsmanship and its historical importance and context. The meticulously restored jewels can be found in precise detail in family portraits. These reflect the social standing of the wearer and illustrate the different ways to wear specific items.

Surviving inventory lists, sketches, correspondence and wills document the occasion on which each individual item of jewellery was created, as well as its value at the time. Unfortunately the goldsmith workshops that made the jewellery are largely unknown.

Sparkling Fashion

In the second half of the 17th century the collection was extended considerably under Prince Paul I. Esterházy. He travelled all the way to Munich and Northern Italy to make his purchases. These were trips of inspiration: he chose the pieces himself in order to add to his “treasure chamber” in remote Forchtenstein.

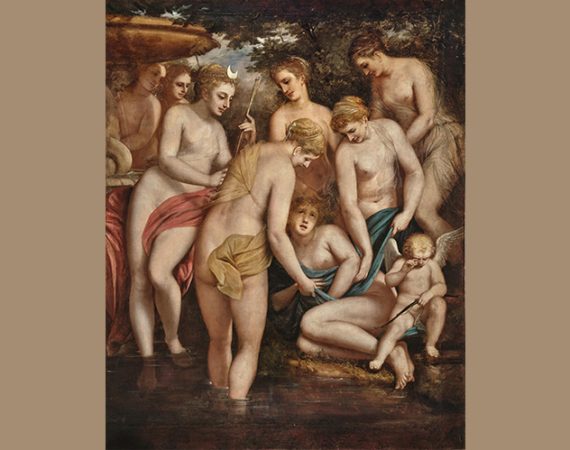

In the 17th century, parures with diamonds and pearls were the height of fashion: these sets of combinable jewellery could be worn in a variety of ways. Mostly they consisted of breast pieces that could be worn as pendants, brooches in the hair, necklaces, pendant earrings and bracelets with hanging parts that were easy to detach. Combined with precious fabrics, they turned their wearer into a work of art.

Bow-shaped brooches, also known as “sévigné brooches”, were particularly popular. They were named after the Marquise de Sévigné, who from the court of Louis XIV kicked off a real “bow-tie boom” all over Europe.

Many of the existing items of jewellery, sketch drawings and, above all, portraits provide impressive proof that the grand wives of the Princes of Esterházy had a special preference for pearls – which were, after all, symbols of purity and perfect female beauty.

In these pieces of jewellery, the pearls, with a hole drilled into them from both sides, were attached with wire or sewn directly onto dresses, caps or cloaks. “Pearl collectors” prevented any falling pearls from rolling into cracks in the floor, while “pearl stitchers” immediately sewed them back in place. Even tiny pearls were so valuable that unused pearls were placed carefully in different containers and stored in case of need. The stern expression of Countess Ursula Esterhá zy indicates how heavy these countless strings of pearls actually were.

The Secret Art of Glass Beads

Glass beads were also considered special in the 17th century: at the French court, these mostly bright and colourful stones from Murano were highly prized. Louis XIV, for example, is said to have sent spies to the Italian island to discover every last secret of the art of creating glass beads. The exceptional craftsmanship of those glass makers can be seen in the pendant from this collection with a picture frame on its back as well as in other beads that were loosely stored. In order to avoid any damage or loss, there was a detailed list of every piece of jewellery, which family member was wearing it and on what occasion.

But the items of jewellery were no more valuable than the jewel cases and small bags they disappeared into once the festive occasion was over. Every individual piece of jewellery had its own special place. The forms and recesses in the shaped cases indicate treasures that have gone missing or no longer exist.

In its entirety the collection of Baroque jewellery at Forchtenstein Castle provides an extraordinary insight into the historically important world of rare gold work that was unique in its historic context.